Notes (edit)

- ↑ A. I. Ivanov. Agaricomycetes of the Volga Upland. Boletales order. - Penza: RIO PGSKhA, 2014 .-- P. 134 .-- 178 p. - ISBN 5-94338-660-2.

- Pelle Jansen. All about mushrooms. - Vilnius: Akritas, 2009 .-- P. 143 .-- 159 p. - ISBN 5-306-00350-8.

- L. G. Perevedentseva. Abstract of agaricoid basidiomycetes of the Perm region. - Perm: PGPU, 2008 .-- P. 40 .-- 86 p. - ISBN 5-85218-375-X.

- ↑ M. Korhonen, J. Hyvönen, T. Ahti. Suillus grevillei and S. clintonianus (Gomphidiaceae), two boletoid fungi associated with Larix (English) // Karstenia: journal. - 1993. - Vol. 33. - P. 1-9.

- ↑ J. A. Muñoz. Boletus s.l. (excl. Xerocomus). - Alassio, 2005. - P. 201-204. - 951 p. - (Fungi Europaei). - ISBN 88-901057-6-3.

- A. H. Smith, H. D. Thiers. A Contribution Toward a Monograph of North American Species of Suillus. - Ann Arbor, 1964. - P. 10-11. - 116 p.

- M. Gill, W. Steglich. Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products. - P. 7, 30, 51.

- A. E. Bessette, O. K. Miller, A. R. Bessette. H. H. Miller. Mushrooms of North America in Color. - 1995. - P. 14-15. - 172 p. - ISBN 0-8156-2666-5.

- ↑ C. H. Peck. Report of the Botanist (unspecified) // Twenty-Third Annual Report of the Regents of the University of the State of New York, on the Condition of the State Cabinet of Natural History. - 1873. - S. 128-129.

- E. E. Both, B. Ortiz-Santana. Clinton, Peck and Frost - the dawn of North American boletology // Bulletin of the Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences: journal. - 2010. - Vol. 39. - P. 11-28.

- C. H. Peck. New York Species of Viscid Boleti (English) // Bulletin of the New York State Museum of Natural History. - 1887. - Vol. 1, no. 2. - P. 60-61.

- C. H. Peck. Boleti of the United States (English) // Bulletin of the New York State Museum. - 1889. - Vol. 2, no. 8. - P. 88.

- C. H. Peck. Report of the State Botanist: 1898 (English) // Bulletin of the New York State Museum. - 1899. - Vol. 5, no. 25 .-- P. 682.

- W. A. Murrill. The Boletaceae of North America: I (English) // Mycologia. - Bulgarian Mycological Society, 1909. - Vol. 1, no. 1. - P. 4-18.

Dry and wet

Even Soloukhin noticed that the popular thought chose the most benign epithet to address the oil can. A mushroom with a permanently slimy-sticky cap could have a very different name. Take at least the same mokruha, which is related to the butterdish. But the people judged differently.

At the same time, in the popular consciousness, the key feature of the butterdish, which gave the name to the whole family, must be rigorously eliminated. Many to this day, with manic-depressive stubbornness, remove the sticky skin from the cap of each mushroom, sometimes sitting up with boletus until the first roosters. Meaning? .. Okay, when you cook a ceremonial dish, where every mushroom is a cucumber ... but so, in ordinary circumstances? .. I don’t understand.

If the oiler were my "natural mushroom", if I, imitating adults, at the age of five for the first time in my life peeled off the skin from my first oiler, such questions would not arise. And so - they arise.

From a crooked (but this is only in summer) yellowish-marsh oiler, you will probably go crazy to remove the skin (photo by I. Lebedinsky)

At the same time, the people do not hold dry-headed representatives of the genus Suillus for boletus. A goat in young pines sometimes grows in such quantity that at least graze the cows on it; yellow-brown oiler flywheel is not so abundant, but rather corpulent, and unlike other representatives of the genus, it is not so attached to young pine - it grows in mature ones. Mushrooms are very different, and they are united, except for a dry cap, one thing - they do not take it.

They do not take, perhaps because they do not need to be cleaned - and some primordial connection with the wisdom of ancestors is broken. In any case, pickled goats and yellow-brown ones are in no way inferior to "noble" boletus, which is easily proved in the course of a blind test.

Anyway, thank you so much for that.

The goat sometimes grows in piles, as if it imagines itself to be a load (photo by I. Lebedinsky)

Definitioner

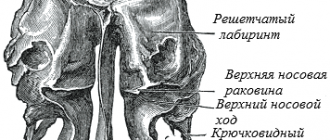

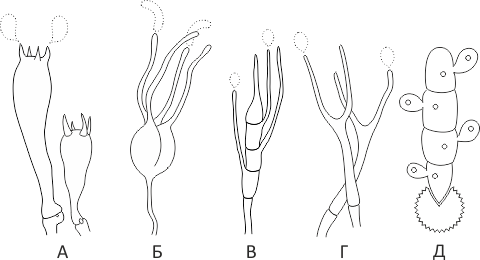

- Basidia (Basidia)

-

Lat. Basidia. A specialized structure of sexual reproduction in fungi, inherent only in Basidiomycetes. Basidia are terminal (end) elements of hyphae of various shapes and sizes, on which spores develop exogenously (outside).

Basidia are diverse in structure and method of attachment to hyphae.

According to the position relative to the axis of the hypha, to which they are attached, three types of basidia are distinguished:

Apical basidia are formed from the terminal cell of the hypha and are located parallel to its axis.

Pleurobasidia are formed from lateral processes and are located perpendicular to the axis of the hypha, which continues to grow and can form new processes with basidia.

Subasidia are formed from a lateral process, turned perpendicular to the axis of the hypha, which, after the formation of one basidium, stops its growth.

Based on morphology:

Holobasidia - unicellular basidia, not divided by septa (see Fig. A, D.).

Phragmobasidia are divided by transverse or vertical septa, usually into four cells (see Fig. B, C).

By type of development:

Heterobasidia consists of two parts - hypobasidia and epibasidia developing from it, with septa (see Fig.C, B) or without them (see Fig. D).

Homobasidia is not divided into hypo- and epibasidia and in all cases is considered holobasidia (Fig. A).

Basidia is the place of karyogamy, meiosis and the formation of basidiospores. Homobasidia, as a rule, is not functionally divided, and meiosis follows karyogamy in it. However, basidia can be divided into probasidia - the site of karyogamy and metabasidia - the site of meiosis. Probasidium is often a dormant spore, for example in rust fungi. In such cases, probazidia grows with metabasidia, in which meiosis occurs and on which basidiospores are formed (see Fig. E).

See Karyogamy, Meiosis, Gifa.

- Pileipellis

-

Lat. Pileipellis, skin - differentiated surface layer of the cap of agaricoid basidiomycetes. The structure of the skin in most cases differs from the inner flesh of the cap and may have a different structure. The structural features of pileipellis are often used as diagnostic features in descriptions of fungi species.

According to their structure, they are divided into four main types: cutis, trichoderma, hymeniderma and epithelium.

See Agaricoid fungi, Basidiomycete, Cutis, Trichoderma, Gimeniderm, Epithelium.

Taxonomy

The species was first described by the American mycologist Charles Horton Peck (1833-1917) in the 1869 Annual Botanical Report of the Museum of Natural History of the State of New York, published in 1872 (the title page indicates 1873, when the entire report appeared, botanical part).

Portrait of George William Clinton, after whom the mushroom is named

Peck placed this mushroom in a composite genus of fleshy tubular mushrooms. Boletus... He named this species after the amateur naturalist Clinton. George William Clinton (1807-1885) - New York politician, lawyer, judge and writer, mayor of the city of Buffalo in 1842-1843, for 20 years headed the Buffalo Natural Science Society. In 1867, Peck, then teaching at a high school in Albany, lost his job due to the closure of the school. Soon Clinton, head of the State Natural History Service (State Cabinet of Natural History), secured him a job as chief botanist of New York. It was in this position that Peck, who had previously studied the bryoflora of New York, became interested in mushrooms and, already in 1869, published his first significant publication on mycology with 53 new species.

Samples of Clinton's oiler were collected in the vicinity of North Elba. in Essex County in northeastern New York State. The holotype is at the New York State Museum.

Clinton's butter dish. Drawing by C. H. Peck (1900). Shown color variability

Peck has repeatedly described subsequent finds of this species. In 1887, he first pointed out its proximity to the larch oiler (called by him Boletus elegans). He thought Boletus clintonianus American "analogue" of the European type Boletus elegans, indicating a number of differences: a darker color, a durable ring that does not disappear with old age, and a leg devoid of any speckling. In 1889, Peck expanded on the variability of the color of Clinton's oiler, which in open places, in his opinion, often grows with a yellow or reddish-yellow cap. Peck distinguished such light-colored fruiting bodies, in addition to the indicated features of the legs and rings, by longer and darker than those of Boletus elegans (which by this time he no longer referred to a purely European species), disputes. In synonyms, he brought the name Boletus viridarius Frost, in 1909 he considered it an independent species. In 1899, Peck published another, more detailed, description Boletus clintonianus.

W.A. Merrill (1909, 1910, 1914) interpreted Boletus clintonianus very broadly, reducing the names Boletus serotinus Frost and Boletus viridarius Frost to synonyms. He considered the main difference between this changeable species and other butterflies with a ring on a stem to be the absence of specks on the stem both above the ring and under it.

To the genus Suillus the species translated in 1898, known for its radical views on botanical nomenclature and giving this generic name priority over Boletus German scientist Otto Kunze (1843-1907). Later, when the genera were taxonomically delineated, this species remained in the genus Suillus.

Since the second half of the 20th century, Clinton's oiler has been referred to in most North American publications as synonyms for larch oiler, only a few have described an independent variety of Suillus grevillei var. clintonianus. In Northern Europe, where attempts were made to isolate the dark oiler attached to larch into an independent taxon, Suillus clintonianus most often referred to under the name Suillus grevillei var. badius. The type specimens of this taxon were collected in 1937 by R. Singer and L.N. Vasilieva in the Chui Alps (Altai). This name is not valid for the purposes of the International Code of Nomenclature.

In 1993, the Finnish mycologists Mauri Korhonen (Fin.) Russian, Jaakko Hyuvenen and Teuvo Ahti (Fin.) Russian. identified clear morphological differences between species, recognizing them as independent. Molecular phylogenetic studies that could confirm or deny the legality of differentiation of species in a complex S. grevilleiwere not carried out.

Synonyms edit code

Homotypic (nomenclature) synonyms:

- Boletinus grevillei var. clintonianus (Peck) Pomerl., 1980, nom. inval.

- Boletus clintonianus Peck, 1872basionym

- Suillus grevillei var. clintonianus (Peck) Singer, 1951

Heterotypic (taxonomic) synonyms:

- Ixocomus elegans f. badius Singer, 1938, nom. inval.

- Suillus grevillei f. badius (Singer) Singer, 1965, nom. inval.

- Suillus grevillei var. badius (Singer) Watling, 1970, nom. inval.

Ecology and distribution

Siberian larch is the tree under which Clinton's oiler is most often found

Clinton's Oily is a boreal fungus that forms mycorrhiza with various species of larch, most often with Siberian larch.

In Russia, it is known in the north of the European part (rarely), Siberia and the Far East (much more often), in the south it comes only into mountain regions (Ural Mountains, Altai Mountains), usually with Siberian and Gmelin larch. Also found in the mountainous regions of China, where larch is found.

Probably brought to Europe with Siberian larch seedlings from Russia. In Scandinavia, it grows in the plantings of Siberian larch in Finland and Sweden (in the northern parts of Finland - more often larch oil can). In Great Britain, it is known from under the hybrid larch Larix × marschlinsii, also found in the Faroe Islands and in the mountainous regions of Switzerland.

Widespread in North America, from where it was originally described. In the eastern part of the mainland, it is found less often than the larch oilweed, and in the western part, on the contrary, it is more common.

Drawing by C. H. Peck, attached to the original description of the species (1872)

Population census

So, what are these 7-8 species of boletus from one forest in the east of the Moscow region? The people should know their heroes.

1. Granular butter dish (Suillus granulatus)... Usually - the first of the boletus, it is distinguished by the absence of a ring, white milky juice protruding from the tubes, and a pronounced "granularity" of the leg. It grows with young pines, comes out among the first, is swept away clean by insect larvae and "natural mushroom pickers".

Particularly bright grainy boletus from the south of the country (photo by user Margot)

Particularly bright grainy boletus from the south of the country (photo by user Margot)

2. Real butter dish (late, yellow, ordinary) - Suillus luteus... Grows in young pines together with granular, usually starting a little later; the cap is darker in color; on the stem there is a clearly pronounced ring remaining from a private veil covering the hymenophore. "Natural mushroom pickers" arrange massive raids on him.

Well, this oiler won't surprise anyone (photo by SVT user)

3. Unordered or ginger butter dish (Suillus collinitus)... Then and there. It looks like a real oiler, but has no ring. "Natural mushroom pickers" do not distinguish it from the first two.

And this oiler can be pretty big (photo by user Margot)

And this oiler can be pretty big (photo by user Margot)

4. Larch Butter (Suillus grevillei)... It forms mycorrhiza with young larch, although - very rarely - it also occurs with spruce. There is a ring, no juice. The not very slippery mushroom of a cheerful yellow color does not enjoy the great love of "natural mushroom pickers", although sometimes they condescend to it.

In adulthood, the larch butterdish is not so effective (photo by I. Lebedinsky)

In adulthood, the larch butter dish is not so effective (photo by I. Lebedinsky)

5. Clinton's Oiler, or Belted (Suillus clintonianus) also grows with larch trees; today science considers it to be a special form of the previous kind, "but this is not accurate."A beautiful chocolate brown hat and a blue leg on the cut make it special. They don't.

Clinton's oilers look like a very special mushroom (photo by I. Lebedinsky)

Clinton's oilers look like a very special mushroom (photo by I. Lebedinsky)

6. Goat (Suillus bovinus) - also pine. A nondescript mushroom with gray-brown caps and a characteristic tubular layer (young pores are extremely small, mature like a sieve) grows in characteristic heaps; abroad it is sometimes called "cow butterdish", meaning its abundance. "Natural mushroom pickers" angrily trample the goat.

A young goat - the very plainness (photo by I. Lebedinsky)

A young goat - the very plainness (photo by I. Lebedinsky)

7. Yellow-brown flywheel (Suillus variegatus) also has a dry cap; it is distinguished by its heroic dimensions by oil standards, as well as the fact that it gravitates towards mature spruce trees. "Natural mushroom pickers" do not pay attention to it, although sometimes they will cut it off and abandon it.

Here he is, yellow-brown (photo by I. Lebedinsky)

Here he is, yellow-brown (photo by I. Lebedinsky)

8. Yellowish or marsh butter dish (Suillus flavidus) grows in damp pine forests. A yellowish-gray cap with a central tubercle, a long winding leg that lifts the mushroom over the mosses, an inexpressive ring on the leg - the mushroom looks rather disgusting, which is only good for us, given that it lingers more often than other relatives until the autumn cold. "Natural mushroom pickers", thank God, have no idea about the swamp butterdish.

In late autumn, a yellowish swamp butterdish can be monumental (photo by I. Lebedinsky)

In late autumn, a yellowish swamp butterdish can be monumental (photo by I. Lebedinsky)

In late autumn, a yellowish swamp butterdish can be monumental (photo by I. Lebedinsky)

... A year has passed since that fruitful trip; this season does not yet have any records for boletus, but I still believe that eight species per day is not the limit. There is a gray larch oil can in the world (Suillus viscidus) - it must be, this is not at all such a rarity! A yellowish marsh oiler is much more difficult to find. So the record will not live long. I believe.

What do we know about the oiler

How many types of butter do we know? Old Soviet reference books, which “natural mushroom pickers” like to refer to, numbered two or three species: granular, late and, on big holidays, larch. True, the goat was often mentioned in the reference books, but as a rule its close connection with the oil can world remained behind the scenes.

And this is Clinton's oiler - not so rare (photo by Igor Krom)

What is it really? Once, for the sake of curiosity, I counted how many species of the genus Suillus (greasers) I met while walking in the famous forest of the Voskresensky district (a young pine-tree mixed with larch - well, everyone knows). It turned out 8-9 types, depending on how you count Clinton's oilers - a separate species or not. A goat and a yellow-brown flywheel (which is also an oil can in the soul) - I counted. And yes, there is no guarantee that I have found - and identified - all the species there. For example, I have not seen a gray larch oil can, although they say that it should be there.

On the site "Mushrooms of Siberia" there are twenty types of boletus. In the photo gallery of our Forum "Mushrooms of the Middle Strip" - fifteen, and they do not intersect completely. According to some estimates, up to thirty species of this genus can be found in Russia, and at least half of them are very good.

And this is an oiler. Have you seen one? Here I am not (photo by Igor Krom)

Many thanks to the old Soviet reference books! "Natural mushroom pickers" collect two or three types of butter, and all the rest, which are no worse, remain to us. It can be very tempting to walk after the Sonder-team, combing a chain of pine trees, and calmly collect valuable mushrooms that these wonderful people simply do not know how to notice.

The census of eastern boletus is further, but for now, let me say a few words about the high.