Taxonomy

This species was first described as Cantherellus floccosus in 1834 by American mycologist Lewis David de Schweinitz, who reported it growing in beech woods in Mount Pocono, Pennsylvania. Its specific epithet is derived from the Latin floccus, meaning "flock of wool". In 1839, Miles Joseph Berkeley described a specimen from Canada as Cantharellus canadensis from a manuscript by Johann Friedrich Klotzsch, noting its affinity to C. clavatus... A large specimen collected in Maine by Charles James Sprague was described as Cantharellus princeps in 1859 by Berkeley and Moses Ashley Curtis.

In 1891, German botanist Otto Kuntze published Revisio Generum Plantarum, his response to what he perceived as a lack of method in existing nomenclatural practice. Three taxa received new names: Kuntze coined the genus Trombetta, which incorporated Cantharellus canadensis (as Trombetta canadensis), while C. floccosus and C. princeps became Merulius floccosus and M. princeps respectively. However, Kuntze's revisionary program was not accepted by the majority of botanists.

Franklin sumner earle made C. floccosus the type species of the new genus Turbinellus in 1909, remarking that “They constitute a striking and well-marked genus which seems to have more in common with the club-shaped species of Craterellus than with the following genus where they have always been placed. " However this was not widely taken up. Earle's new combination was not published validly according to nomenclatural rules.

In 1945 it was transferred to Gomphus by Rolf Singer. The generic name is derived from the Ancient Greek γομφος, gomphos, meaning "plug" or "large wedge-shaped nail". Alex H. Smith treated the members of Gomphus as two sections—Gomphus and Excavatus—Within Cantharellus in his 1947 review of chanterelles in western North America, as he felt there were no consistent characteristics that distinguished the genera. The shaggy chanterelle was placed in the latter section due to its scaly cap, lack of clamp connections and rusty-colored spores. Roger Heim classified it in the genus Nevrophyllum, before E. J. H. Corner returned it to Gomphus in 1966.

The genus Gomphus, along with several others in the Gomphaceae, was reorganized in the 2010s after molecular analysis confirmed that the older morphology-based classification did not accurately represent phylogenetic relationships. Thus the genus Turbinellus was resurrected and the taxon became Turbinellus floccosus.

T. floccosus has been given the common names of scaly vase chanterelle,scaly chanterelle, woolly chanterelle, or shaggy chanterelle, though it is more closely related to stinkhorns than true chanterelles. In Nepal, in the Sherpa language, it is known as diyo chyau or khumbhe chyau, from the words diyo, meaning "oil lamp" and chyau, meaning "mushroom", as the fruit bodies have a shape similar to the local oil lamps. In Mexico, it is known as corneta or trompeta, or by the indigenous words Tlapitzal, tlapitzananácatl or oyamelnanácatl in Tlaxcala.

Description

File: Gomphus floccosus spores.jpg

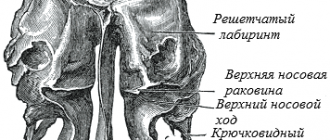

Oval spores in Melzer's solution, seen through a microscope

Adult fruit bodies are initially cylindrical, maturing to trumpet- or vase-shaped and reaching up to 30 cm (12 in) high and up to 30 cm (12 in) across. There is no clear demarcation between the cap and stipe. The stipe itself can be up to 15 cm (6 in) tall and 6 cm (2.4 in) wide, though it tapers to a narrower base. It is solid in younger specimens, though is often hollowed out by insect larvae in older. At higher elevations, two or three fruit bodies may arise from one stipe. Colored various shades of reddish- to yellowish-orange, the cap surface is broken into scales, with the spaces between more yellow and the scales themselves more orange. The most colorful specimens occur in warm humid weather. Older specimens are often paler.

The white flesh is fibrous and thick, though thins out in old specimens. Somewhat brittle, it can sometimes turn brown when cut or bruised. The smell has been reported as indistinct or "earthy and sweet", and the taste "sweet and sour". The spore-bearing undersurface is irregularly folded, forked or ridged rather than gilled and is pale buff or yellowish to whitish in color. These ridges are up to 4 mm high. The surface is decurrently attached to the stipe, though irregularly so. The spore print is brownish, the spores ellipsoid with dimensions of 12.4–16.8 x 5.8–7.3 μm. The spore surface is roughened with ornamentations that can be made visible under the microscope by staining with methyl blue.

The fruit bodies can last for some considerable time, growing slowly over a month. Mushrooms in subalpine and alpine areas are typically heavy-set with a short stipe, their growth slower in the cold climate. This form is slower growing, and is seen at lower altitudes in colder seasons. Smith gave this the name forma rainierensis... Conversely, mushrooms at low altitudes, such as in the redwood forests, can grow and expand rapidly with large caps that have prominent scales. Smith described a paler form with a solid stipe from the Sierra Nevada as forma wilsonii... R. H. Petersen described an olive-capped form that is otherwise identical to the typical form. These forms are not recognized as distinct.

Similar species

Lookalikes

145px

Turbinellus fujisanensis

159px

Turbinellus kauffmanii

The related Turbinellus kauffmanii, found in western North America, is similar-looking but has a pale brown cap. Younger specimens of the latter species also have a pungent smell.Turbinellus fujisanensis, found in Japan, is another lookalike that has smaller spores than T. floccosus... The fruit bodies of Gomphus bonarii, found in northwestern North America, are typically more yellowish to brownish compared to T. floccosus, and they tend to fruit in clumps.

References []

- Simpson DP (1979). Cassell's Latin Dictionary (5th ed.). London: Cassell. p. 883. ISBN 978-0-304-52257-6.

- ^

- ^

- ^

- Singer R. (1945). New Genera of Fungi. Lloydia. 8: 139–44.

- ^

- ^

- Bessette AE, Fischer DW, Bessette AR (1996). Mushrooms of Northeastern North America... Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8156-0388-7.

- ^

- Tylutki E (1987). Mushrooms of Idaho and the Pacific Northwest: Non-gilled Hymenomycetes... Moscow: University Press of Idaho. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-89301-097-3.

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^

- ^ Ammirati JF, Traquair JA, Horgen PA (1985). ... Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. –54. ISBN 978-0-8166-1407-3.

- ^

- ^ Petersen DH (1971). "The genera Gomphus and Glococantharellus in North America ". Nova Hedwigia. 21: 1–118.

- Roberts P, Evans S (2011). The book of fungi... Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 483. ISBN 978-0-226-72117-0.

- ^ Corner EJH (1966). "A Monograph of the Cantharelloid Fungi". Annals of Botany Memoirs... London: Oxford University Press. 2: 1–255.

- Masui K (1926). “A Study of the Mycorrhiza of Abies firma, S. et Z., with Special Reference to its Mycorrhizal Fungus Cantharellus floccosus, Schw ". Memoirs of the College of Science. Kyoto Imperial University. Series B. 2 (1): 1–84.

- Wojewoda W, Heinrich Z, Komorowska H (1993). "Macrofungi of North Korea". Wiadomości Botaniczne. 37 (3/4): 125–28.

- Verma RN, Singh SM, Singh TG, Bilgrami KS (1989). "Gomphus floccosus - A New Record for India ". Current Science. 58 (24): 1370–71.

- Fuhrer BA (2005). A Field Guide to Australian Fungi... Melbourne, Victoria: Bloomings Books. p. 206. ISBN 978-1-876473-51-8.

- Smith AH, Weber NS (1980). The Mushroom Hunter's Field Guide... Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-472-85610-7.

- ^

- ^ Khaund P, Joshi SR (2014). "The Gomphus Paradox of Meghalaya: Wild Edible Fungus or a Poisonous Mushroom? " In Kharwar RN, Upadhyay RS, Dubey NK, Raguwanshi R (eds.). Microbial Diversity and Biotechnology in Food Security... New Delhi: Springer India. pp. 171–76. ISBN 978-81-322-1800-5.

Taxonomy []

This species was first described as Cantherellus floccosus in 1834 by American mycologist Lewis David de Schweinitz, who reported it growing in woods in Mount Pocono, Pennsylvania. Its specific epithet is derived from the Latin floccus, meaning "tuft, or flock, of wool". In 1839, Miles Joseph Berkeley named a specimen from Canada as Cantharellus canadensis based on a manuscript by Johann Friedrich Klotzsch, noting its affinity to C. clavatus... A large specimen collected in Maine by Charles James Sprague was described as Cantharellus princeps in 1859 by Berkeley and Moses Ashley Curtis. In 1891, German botanist Otto Kuntze renamed Cantharellus canadensis as Trombetta canadensis, and C. floccosus as Merulius floccosus.

Franklin sumner earle made C. floccosus the type species of the new genus Turbinellus in 1909, in which he placed two other North American species. He remarked that the three «constitute a striking and well-marked genus which seems to have more in common with the club-shaped species of Craterellus than with the following genus where they have always been placed. " This was not widely taken up, as Earle's new combination was not published validly according to nomenclatural rules.

American mycologist Elizabeth Eaton Morse described Cantharellus bonarii in 1930. The type locality was General Grant National Park in Fresno County, California. In 1945 C. floccosus and Morse’s C. bonarii were transferred to Gomphus by Rolf Singer. The generic name is derived from the Ancient Greek γομφος, gomphos, meaning "plug" or "large wedge-shaped nail". Alex H. Smith treated the members of Gomphus as two sections—Gomphus and Excavatus—Within Cantharellus in his 1947 review of chanterelles in western North America, as he felt there were no consistent characteristics that distinguished the genera. The shaggy chanterelle was placed in the latter section due to its scaly cap, lack of clamp connections and rusty-colored spores. Roger Heim classified it in the genus Nevrophyllum, before E. J. H. Corner returned it to Gomphus in 1966.

The genus Gomphus, along with several others in the Gomphaceae, was reorganized in the 2010s after molecular analysis confirmed that the older morphology-based classification did not accurately represent phylogenetic relationships. Thus the genus Turbinellus was resurrected and the taxon became Turbinellus floccosus... Giachini also concluded G. bonarii was the same species.

T. floccosus has been given the common names of scaly vase chanterelle,scaly chanterelle, woolly chanterelle, or shaggy chanterelle, though it is more closely related to stinkhorns than true chanterelles. In Nepal, in the Sherpa language, it is known as diyo chyau or khumbhe chyau, from the words diyo, meaning "oil lamp" and chyau, meaning "mushroom", as the fruit bodies have a shape similar to the local oil lamps. In Mexico, it is known as corneta or trompeta, or by the indigenous words oyamelnanácatl ("Fir mushroom", from Nahuatl oyametl "Fir", and nanacatl "Mushroom"), tlapitzal (derived from tlapitzalli, Nahuatl for "trumpet") or tlapitzananácatl in Tlaxcala.

Description

Oval spores in Melzer's solution, seen through a microscope

Adult fruit bodies are initially cylindrical, maturing to trumpet- or vase-shaped and reaching up to 30 cm (12 in) high and up to 30 cm (12 in) across. There is no clear demarcation between the cap and stipe. The stipe can be up to 15 cm (6 in) tall and 6 cm (2.4 in) wide, though it tapers to a narrower base. It is solid in younger specimens, though is often hollowed out by insect larvae in older. At higher elevations, two or three fruit bodies may arise from one stipe. Colored various shades of reddish- to yellowish-orange, the cap surface is broken into scales, with the spaces between more yellow and the scales themselves more orange. The most colorful specimens occur in warm humid weather. Older specimens are often paler.

The white flesh is fibrous and thick, though thins with age. Somewhat brittle, it can sometimes turn brown when cut or bruised. The smell has been reported as indistinct or "earthy and sweet", and the taste "sweet and sour". The spore-bearing undersurface is irregularly folded, forked or ridged rather than gilled and is pale buff or yellowish to whitish in color. These ridges are up to 4 mm (1⁄8 in) high, and are decurrent — they extend below and run down the cap's attachment to the stipe, though irregularly so. The spore print is brownish, the spores ellipsoid with dimensions of 12.4–16.8 × 5.8–7.3 μm. The spore surface is roughened with ornamentations that can be made visible under the microscope by staining with methyl blue.

The fruit bodies can last for some considerable time, growing slowly over a month. Mushrooms in subalpine and alpine areas are typically heavy-set with a short stipe, their growth slower in the cold climate. This latter form is seen at lower altitudes in colder seasons. Smith gave this the name forma rainierensis... Conversely, mushrooms at low altitudes, such as in the redwood forests, can grow and expand rapidly with large caps that have prominent scales. Smith described a paler form with a solid stipe from the Sierra Nevada as forma wilsonii... American mycologist R. H. Petersen described an olive-capped form that is otherwise identical to the typical form. These forms are not recognized as distinct.

Similar species

Lookalikes

Turbinellus fujisanensis

Turbinellus kauffmanii

The related Turbinellus kauffmanii, found in western North America, is similar-looking but has a pale brown cap. Younger specimens of the latter species also have a pungent smell.Turbinellus fujisanensis, found in Japan, is another lookalike that has smaller spores than T. floccosus.

Taxonomy [edit]

This species was first described as Cantherellus floccosus in 1834 by American mycologist Lewis David de Schweinitz, who reported it growing in woods in Mount Pocono, Pennsylvania. Its specific epithet is derived from the Latin floccus, meaning "tuft, or flock, of wool". In 1839, Miles Joseph Berkeley named a specimen from Canada as Cantharellus canadensis based on a manuscript by Johann Friedrich Klotzsch, noting its affinity to C. clavatus... A large specimen collected in Maine by Charles James Sprague was described as Cantharellus princeps in 1859 by Berkeley and Moses Ashley Curtis. In 1891, German botanist Otto Kuntze renamed Cantharellus canadensis as Trombetta canadensis, and C. floccosus as Merulius floccosus.

Franklin sumner earle made C. floccosus the type species of the new genus Turbinellus in 1909, in which he placed two other North American species. He remarked that the three «constitute a striking and well-marked genus which seems to have more in common with the club-shaped species of Craterellus than with the following genus where they have always been placed. " This was not widely taken up, as Earle's new combination was not published validly according to nomenclatural rules.

American mycologist Elizabeth Eaton Morse described Cantharellus bonarii in 1930. The type locality was General Grant National Park in Fresno County, California. In 1945 C. floccosus and Morse’s C. bonarii were transferred to Gomphus by Rolf Singer. The generic name is derived from the Ancient Greek γομφος, gomphos, meaning "plug" or "large wedge-shaped nail". Alex H. Smith treated the members of Gomphus as two sections—Gomphus and Excavatus—Within Cantharellus in his 1947 review of chanterelles in western North America, as he felt there were no consistent characteristics that distinguished the genera. The shaggy chanterelle was placed in the latter section due to its scaly cap, lack of clamp connections and rusty-colored spores. Roger Heim classified it in the genus Nevrophyllum, before E. J. H. Corner returned it to Gomphus in 1966.

The genus Gomphus, along with several others in the Gomphaceae, was reorganized in the 2010s after molecular analysis confirmed that the older morphology-based classification did not accurately represent phylogenetic relationships. Thus the genus Turbinellus was resurrected and the taxon became Turbinellus floccosus... Giachini also concluded G. bonarii was the same species.

T. floccosus has been given the common names of scaly vase chanterelle,scaly chanterelle, woolly chanterelle, or shaggy chanterelle, though it is more closely related to stinkhorns than true chanterelles. In Nepal, in the Sherpa language, it is known as diyo chyau or khumbhe chyau, from the words diyo, meaning "oil lamp" and chyau, meaning "mushroom", as the fruit bodies have a shape similar to the local oil lamps. In Mexico, it is known as corneta or trompeta, or by the indigenous words oyamelnanácatl ("Fir mushroom", from Nahuatl oyametl "Fir", and nanacatl "Mushroom"), tlapitzal (derived from tlapitzalli, Nahuatl for "trumpet") or tlapitzananácatl in Tlaxcala.

Taksonomi

Bu tür ilk edildi açıklandığı şekilde Cantherellus floocosus Amerikan mikelog tarafından 1834 yılında Lewis David de Schweinitz o büyüyen bildirilen, ormanda Mount Pocono, Pensilvanya. Onun özel bir sıfat türetilir Latince miseliy "Tutam veya flok, yün" anlamına. 1839 yılında Miles Joseph Berkeley olarak Kanada’dan bir örnek adında Cantharellus canadensis tarafından kopyasına dayanarak Johann Friedrich Klotzsch olan ilgisi belirterek, C. clavatus ... Tarafından Maine toplanan büyük örnek Charles James Sprague olarak nitelendirildi Cantharellus princeps'in Berkeley ve tarafından 1859 yılında Musa Ashley Curtis. 1891'de Alman bitkibilimci Otto Kuntze değiştirildi Cantharellus canadensis olarak Trombetta canadensis ve C floccosus olarak Merulius floccosus .

Franklin Sumner Earle yapılmış C floccosus tip türlerin yeni bir cins arasında Turbinellus başka iki Kuzey Amerika türler yerleştirilmiş olan 1909. Üç “nin kulüp şeklindeki türlerle ortak noktası daha var gibi görünüyor çarpıcı ve iyi işaretlenmiş cins olu beluşirt Craterellus her zaman yerleştirilmiş olan aşağıdaki cinsi olmaktansa. " Earle gibi bu yaygın kabul görmedi yeni kombinasyon yayınlanmadı validly göre isimlendirme kurallarına.

Amerikan mikelog Elizabeth Eaton Morse açıklanan Cantharellus bonarii 1930 yılında tipi mevkiinde idi General Grant Milli Parkı içinde Fresno County, California. 1945'te C. floccosus ve Morse'un C bonarii aktarıldı Gomphus tarafından Rolf Singer. Jenerik ismi türetilmiştir Antik Yunan γομφος, gomphos "Fişi" ya da "büyük kama şeklindeki çivi" anlamına gelen. Alex H. Smith üyelerini tedavi Gomphus iki olarak bölümlere - Gomphus ve excavatus -within cantharellus o cins ayırt hiçbir tutarlı özellikler vardı keçe gibi batı Kuzey Amerika’da chanterelles yaptığı 1947 incelemede. Tüylü tür mantar nedeniyle pullu kapağa ikinci kısmında yerleştirilmiştir, eksikliği kelepçe bağlantıları ve paslı renkli sporların. Roger Heim cinsi sınıflandırdık Nevrophyllum önce EJH Köşe göndermesiyle Gomphus 1966 yılında.

Cinsi Gomphus sonra, Gomphaceae birkaç kişiyle birlikte 2010’lu yıllarda yeniden düzenlenmiş moleküler analiz yaşlı doğruladı morfolojisi doğru temsil etmediğini sınıflandırma tabanlı filogenetik ilişkileri. Böylece cinsi Turbinellus dirildi ve takson oldu Turbinellus floocosus ... Giachini da sonucuna G. bonarii aynı tür olarak belirlenmiştir.

T. floccosus ortak isim verilmiştir pullu vazo chanterelle , pullu chanterelle , yünlü chanterelle veya tüylü chanterelle daha yakından ilişkili olmasına rağmen, stinkhorns daha doğru chanterelles. In Nepal, içinde Sherpa dili, bu olarak bilinen diyo chyau veya khumbhe chyau kelimeler gelen diyo "Kandil" ve anlamı chyau meyve organları yerel kandiller benzer bir şekle sahip olarak, anlamına gelen "mantar". Meksika’da, bu olarak bilinen corneta veya Trompeta , ya da yerli kelime ile oyamelnanácatl (Nahuatl gelen "FIR mantar", oyametl "Köknar" ve nanacatl "Mantar"), tlapitzal (türetilen tlapitzalli , Nahuatl "trompet" için) ya da tlapitzananácatl içinde Tlaxcala'da.

Toxicity

File: Gomphus poison.png

α-tetradecylcitric acid

Turbinellus floccosus is poisonous to some people who eat it, but has been eaten without incident by others. Nausea, vomiting and diarrhea may occur, though are sometimes delayed by up to 8–14 hours. A tricarboxylic acid known as α-tetradecylcitric- or norcaperatic acid may be responsible for the extreme gastrointestinal symptoms. Laboratory experiments showed it increased tone of guinea pig smooth muscle of the small bowel (ileum), and that when given to rats, it led to mydriasis, skeletal muscle weakness, and central nervous system depression. The concentration (4.4%) of the presumed active ingredient — norcaperatic acid — extracted from fruit bodies of Turbinellus floccosus was over double that extracted from the related T. kauffmanii.

Despite its toxicity, T. floccosus is one of the ten wild mushrooms most widely consumed by ethnic tribes in Meghalaya, northeast India, and is highly regarded by the Sherpa people in the vicinity of Sagarmatha National Park in Nepal. What is not known is whether the populations of T. floccosus are lacking in the toxin, or whether the local people have developed an immunity to it. It is also eaten in Mexico. Mycologist David Arora reported some enjoyed it while he felt it had a sour taste that he found off-putting.

The fruit body of T. floccosus produces oxylipin (biologically active lipids generated from fatty acids) that have antifungal activity against the plant pathogens Colletotrichum fragariae, C. gloeosporioides, and C. acutatum... Extracts of the fungus have shown in standard laboratory tests to have antimicrobial activity against several human pathogenic strains.T. floccosus also contains the spermidine derivative pistillarin, a bioactive compound that inhibits DNA damage by hydroxyl radicals generated by the Fenton reaction. Pistillarin is responsible for the green color obtained when are applied to the fruit body surface.

Popis

Oválné spóry v Melzer roztokem, při pohledu přes mikroskop

Dospělý plodnice jsou zpočátku válcové, zrání na trumpet- nebo váza tvaru a dosahující až do 30 cm (12 in), vysoké a až do 30 cm (12 v) v průměru. Není tam žádná jasná hranice mezi víčkem a třeně. Třeně může být až do 15 cm (6 palců) vysoký a 6 cm (2.4 palce) široký, i když se zužuje na užší základně. Je pevná u mladších jedinců, i když je často vyhloubeny larvami hmyzu ve starší. Ve vyšších nadmořských výškách, dva nebo tři plodnice mohou vzniknout z jednoho třeně. Barevný různé odstíny červenohnědý až žluto-oranžové víčko povrch je rozdělen do šupiny, s mezerami mezi žlutější a šupiny samy více oranžové. Nejpestřejší vzorky se vyskytují v teplém vlhkém počasí. Starší jedinci jsou často světlejší.

Bílý tělo je vláknitý a hustý, ačkoli tenčí s věkem. Poněkud křehká, může někdy zhnědnou na řezu nebo pohmoždění. Vůně byla označena jako nevýrazný nebo "zemitý a sladký" a chuť "sladké a kyselé." Tyto hřebeny jsou až 4 mm (1 / 8 palce) vysoko a jsou Decurrent-sahají dále a stékají přílohu SZP do třeně, i když nepravidelně tak. Spore tisk je hnědavý, že spory elipsoidu o rozměrech 12.4-16.8 × 8 / 05-03 / 07 um. Výtrus povrch zdrsnit ozdob, které mohou být zviditelněny pod mikroskopem pomocí barvení s methyl-modří.

Tyto plodnice může trvat nějakou dobu, rostou pomalu během jednoho měsíce. Houby v podhorské a alpských oblastech jsou obvykle podsaditý s krátkou třeně, jejich růst pomalejší v chladném podnebí. Tato posledně uvedená forma je vidět v nižších nadmořských výškách v chladnějších obdobích. Smith dal tento název zálohové rainierensis ... Naopak houby v nízkých výškách, jako například v Borové lesy, mohou růst a expandovat rychle s velkými uzávěry, které mají významné váhy. Smith popsal bledší formu s pevnou stipe z Sierra Nevada jako forma wilsonii ... Americký mykolog RH Petersen popsáno formulář olivový uzávěrem, který je jinak identický s typickou formu. Tyto formy nejsou považovány za odlišné.

Podobné druhy

Vypadat podobně

Turbinellus fujisanensis

Turbinellus kauffmanii

Související Turbinellus kauffmanii , nalezený v západní části Severní Ameriky, je podobný-vypadat, ale má světle hnědou čepici. Mladší jedinci druhých druhy mají také štiplavý zápach. Turbinellus fujisanensis , vyskytuje se v Japonsku, je další lookalike, který má menší výtrusy než T. floccosus .

References

- Simpson DP. (1979). Cassell's Latin Dictionary (5 ed.). London, United Kingdom: Cassell. p. 883. ISBN 978-0-304-52257-6.

- ↑

- ↑

- Singer R. (1945). "New genera of fungi". Lloydia. 8: 139–44.

- Liddell HJ, Scott R. (1980). Greek-English Lexicon, Abridged Edition... Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-910207-5.

- ↑

- ↑

- Bessette AE, Fischer DW, Bessette AR. (1996). Mushrooms of Northeastern North America... Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8156-0388-7.

- ↑ Arora D (1986). Mushrooms Demystified: a Comprehensive Guide to the Fleshy Fungi... Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press. pp. 661-62. ISBN 978-0-89815-169-5.

- Tylutki E (1987). Mushrooms of Idaho and the Pacific Northwest: Non-gilled Hymenomycetes... Moscow, Idaho: University Press of Idaho. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-893-01097-3.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Ammirati JF, Traquair JA, Horgen PA. (1985). Poisonous Mushrooms of the Northern United States and Canada... Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 253-54. ISBN 978-0-8166-1407-3.

- ↑

- ↑ Petersen DH. (1971). "The genera Gomphus and Glococantharellus in North America ". Nova Hedwigia. 21: 1–118.

- Roberts P, Evans S. (2011). The book of fungi... Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 483. ISBN 978-0-226-72117-0.

- McKnight VB, McKnight KH. (1987). A Field Guide to Mushrooms: North America... Peterson Field Guides. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 86-87. ISBN 978-0-395-91090-0.

- Verma RN, Singh SM, Singh TGB, Bilgrami KS (1989). "Gomphus floccosus - a new record for India ". Current Science. 58 (24): 1370–71.

- ↑ Corner EJH (1966). "A Monograph of the Cantharelloid Fungi". Annals of Botany Memoirs. 2... London, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press: 1-255.

- Masui K (1926). “A Study of the Mycorrhiza of Abies firma, S. et Z., with Special Reference to its Mycorrhizal Fungus Cantharellus floccosus, Schw ". Memoirs of the College of Science. Kyoto Imperial University. Series B. 2 (1): 1–84.

- Fuhrer BA (2005). A Field Guide to Australian Fungi... Melbourne, Victoria: Bloomings Books. p. 206. ISBN 978-1-876473-51-8.

- Smith AH, Weber NS (1980). The Mushroom Hunter's Field Guide... Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-472-85610-7.

- Ammirati et al. p. 252

- ↑

- ↑ Khaund P, Joshi SR (2014). "The Gomphus paradox of Meghalaya: wild edible fungus or a poisonous mushroom? " In Kharwar RN, Upadhyay RS, Dubey NK, Raguwanshi R. (eds.) (Ed.). Microbial Diversity and Biotechnology in Food Security... Springer India. pp. 171–76. ISBN 978-81-322-1800-5.