Content [show]

«

Roses of Heliogabalus

". Painting illustrating the story "Stories of the Augustus"

about the fact that at the feast at the emperor

Elagabala

rose petals scattered in such an immoderate amount that some of the guests were suffocating, unable to get out from under the rubble.

Lawrence Alma-Tadema

, 1888

Cuisine and food culture of Ancient Rome formed and changed during the entire period of the existence of the ancient Roman state.

Originally, the food of the ancient Romans was very simple, the culinary art in Rome began to develop from the 3rd century BC. e., later was influenced by ancient Greek culture, then the expansion of the empire contributed to the development of recipes of ancient Roman cuisine and dining traditions. Influenced by oriental fashion and at the same time enriching many Romans, during the era of the empire in Rome, profligacy and gluttony flourished among the rich. The food of the peasant and the senator, the urban artisan and the wealthy freedman, differed from each other, as did the culture of food consumption.

Food

Most Romans ate very simply, their daily food consisted mainly of grain, from which porridge and bread were made. Also, the diet of the Romans included vegetables and fruits. According to late antique authors, bread and wine were the main food products: 66: XX 1, 5. Hunger, in the understanding of the Romans, meant that the main food product, grain, was running out, as evidenced by the discontent and uprisings of the population due to the lack of bread or crop failure. There is no evidence of a single uprising due to lack of meat, fish or vegetables: 20.

Some cities and provinces were famous for their products: for example, in Venafro and Casin they produced first-class olive oil, in Pompeii there was a large production of garum, and the best varieties of table olives were supplied to Rome from Picena. In the valley of the Po and Gaul, they produced excellent smoked bacon, pork and ham, oysters were imported from Brundisium, leeks from Tarentum, Ariccia and Ostia, Ravenna was famous for asparagus, Pompeii for cabbage, Lucania for sausage. Dairy products, pigs and lambs, poultry and eggs came to Rome from the surrounding suburban estates, and from the Westin region in Central Italy, from Umbria and Etruria - cheeses. Forests near Lake Tsima and near Lavrenty supplied game in abundance.

Grain and bread

Originally, wheat in ancient Rome meant the emmer, later the emmer was supplanted by cultivated wheat. Rye was almost not widespread in the Mediterranean region, however, due to its frost resistance, from the 2nd century it began to grow more and more in the northern provinces of the empire. Oats were also considered a low-grade grain and were grown primarily as animal feed. According to Pliny, oats were cultivated as a food only in Germany: 82. Barley was used primarily as feed and less often as food: in the early period of Rome, barley porridge was the food of the poor. For legionnaires, the barley diet was considered a punishment: 82.

Bread and flatbreads were not a typical dish of the Romans in the early period of Ancient Rome, the population mainly ate porridge. From the 2nd century BC NS. public bakeries appeared in Rome: 37, and bread very quickly became popular, including among the poor. Over time, the number of types of bread has increased. Usually it was baked in every home, but there were also special bakeries selling round loaves. Famous breads: white wheat from fine flour (panis siligneus / candidus), medium-quality white made from coarser flour (panis secundarius) and black, very hard, from coarse flour (panis plebeius - "folk", rusticus - "peasant", sordidus - "dirty-dark"). The third class also included the legionnaires' bread, which looked more like crackers (panis castrensis - "camp bread"), which they baked for themselves during their stops: 67.

A fresco that is often published under the title "The Bread Trade". Researchers now believe that the fresco depicts

aedile

giving bread to the urban poor

... Fresco from Pompeii.

Depending on the method of preparation, the bread was called oven or podzol - baked under hot ash. They also prepared special types that were in harmony with different dishes in taste, for example, "oyster bread" for seafood dishes; some types of bread and pastries were supplemented with milk, fat, pearl barley, laurel, celery, coriander, anise, poppy seeds, honey, caraway seeds, sesame seeds: 27. The bread was baked in different forms depending on the baker's imagination: cubes, lyres, braids. They even baked bread in the shape of the god Priapus: XIV, 70:60, 4.

Cookies and sweets were made in figured forms in the form of animals, birds, comic figures, rings, pyramids, wreaths, pretzels. Raisins, cheese, almonds were baked into pies. Some of the dishes were deep-fried: globuli - balls of sour dough, fried in olive oil, poured with honey and sprinkled with poppy seeds. Multi-layer cakes were baked (placenta), curds, almond and fruit pies.

Dairy products and eggs

Undiluted milk was considered a barbaric or peasant drink: 7, 2, 2, in cities milk was no longer a basic foodstuff. It was added to baked goods (including some fish and vegetable casseroles), cereals: VI, 9, 12, used to make a sweet omelet: XVII, 13, 2-8. The peasants used primarily sheep and goat milk. Cow's milk was considered the least nutritious, it was used very rarely, donkey and mare's milk was given, most likely, only to the sick: 130-132.

Most types of cheese were very cheap and affordable even for the poor. Goat and sheep cheese was widespread. Cheese was consumed with bread, lard, as part of many recipes; ate fresh, smoked and dried for supplies, the poor prepared a dish from salted fish and cheese - tyrotarichum, cheese paste moretumIn pie recipes, dried cheese was sometimes used instead of flour. In early recipes of ancient Roman cuisine, it was very often included in dishes and even bread. During the imperial period, cheese remained mainly in the recipes of simple cuisine.

The Romans did not know cream, in the Latin language there was not even a word for this product. Butter, which existed in those days only in ghee, remained for the Romans a food product of the barbarians.

Eggs were eaten boiled, soft-boiled, in scrambled eggs and omelettes and used in many other recipes, including baked goods and sauces. In modest farms, mainly chicken eggs were used, less often duck and goose eggs. The gourmet menu also included peacocks, quail, and less often ostrich eggs: 129.

Meat

- Beef was not popular among gourmets, as the cow was used for agricultural work and therefore had tough meat. However, many archaeological excavations have found the remains of slaughtered cows.

- The pork was very popular. Previously, pork was cooked only on major holidays in honor of the gods: 2, 4, 9.All parts were consumed, even those that, from a modern point of view, are rather unsuitable for eating, for example, the udder (boiled and then grilled) and the uterus of a young pig (according to the Apicia recipe - seasoned with pepper, celery seeds and dried mint, sylph, honey, vinegar and garum: XVII, 1, 2: 103), as well as glands, testicles, head, liver, stomach (according to Apicius - best of all a pig fed with figs): VII: 258).

- Sausages were made from beef or pork according to numerous recipes. The simple form was especially widespread botulus - blood sausage that was sold on the street. The most popular was Lucan sausage - smoked pork sausage richly seasoned with spices: II, 4. It is believed that it was first brought by soldiers from southern Italy to Rome; it should be said that similar recipes have survived to this day. For a special effect, pork carcasses were stuffed with sausages and fruits, grilled whole (porcus Troianus).

- Hares and rabbits were also bred, the first, however, with less success, so that the hare cost four times more. Hare was considered a delicacy and for Roman gourmets it was first boiled, then fried in the oven, and only then served with a sauce of pepper, savory, onions, walleye, celery seeds, garum, wine and olive oil: 184.

- Sometimes a whole wild boar was served on the table. Apicius recommended a cold sauce of pepper, lovage, thyme, oregano, cumin, dill seeds, sylphia, wild walleye seeds, wine, onions, toasted almonds, dates, honey, vinegar, olive oil, as well as garum and defrutum for colors: VIII, 1, 8.

Bird

In addition to poultry, pheasants, guinea fowls, and peacocks were bred. During the imperial period, food was consumed: chickens, capons, ducks (the breast and back were especially prominent), geese (iecur ficatum - the liver of an overfed goose acted as an expensive delicacy), storks, cranes, partridges, pigeons, blackbirds, nightingales , hazel grouses, peacocks, pheasants, flamingos, parrots. From blackbirds, for example, a casserole was prepared with the addition of chicken, boiled pork udder, fish fillets and flatbreads with a sauce of eggs, pepper, lovage, olive oil, garum and wine: 190. The more expensive the bird was and the more difficult it was to get it, the more “interesting” it was for a gourmet: XIII, 76.

The fashion for various types of birds also changed, for example, during the time of Martial, hazel grouse became popular: XIII, 62: 186. On the Balearic Islands, they willingly cooked small cranes and buzzards, and from there they exported the sultan to Rome. Gourmet chickens were imported from Rhodes and Numidia, waterfowl from Parthia, peacocks from Babylonia, pheasants from Colchis.

Fish

Mosaic "Inhabitants of the Sea". Pompeii

The price of fish was superior to simple types of meat. The menu of the ancient Romans included the following types of fish: mullet, moray (its fillet was considered especially tasty), sturgeon, flounder, cod, trout, gudgeon, parrot fish, tuna, sea urchins, seabass, scallops and others: 81-90. In the republican period, sturgeon was popular among gourmets, in the era of the late Republic - cod and laurel. Under Tiberius, parrotfish came into fashion, in the time of Pliny the Elder - red mullet, while large fish caught in the open sea were valued: 191. Red mullet was considered a delicacy and even served as the embodiment of luxury for some time. Oysters and lobsters were also prepared.

They tried to breed fish in freshwater and salt ponds, and in rich estates in special piscinas - cages with fresh or with seawater carried through canals. The first organizer of such a pool for fish is Lucius Murena, for oysters - Sergius Orata, for shells - Fulvius Lupin. Luxurious scribes were in the villas of Lucullus and Hortense. Shellfish have also been farmed on a large scale.

The fish was boiled in salt water, grilled, stewed, charcoal, baked and fricassee made. Apicius recommended a sauce of pepper, lovage, egg yolk, vinegar, garum, olive oil, wine, honey for oysters. Oysters, according to Apicius, were suitable for making casseroles from boiled chicken, Lucan sausage, sea urchins, eggs, chicken liver, cod and cheese fillets, as well as vegetables and seasonings: 196.The Romans prepared various hot fish sauces: garum from mackerel, muria from cuffs, alex from the remnants of mackerel and cuffs or from ordinary fish.

Vegetables

Of the vegetables, onions, leeks, garlic, lettuce, turnips, radishes, and carrots were known. Several varieties of cabbage were known; cabbage was consumed raw with vinegar, boiled and eaten with seasonings and salt, with lard. The Swiss chard was eaten with thick white trunks and greens, and served with mustard to lentils and green beans. Asparagus was added to vegetable stews, casseroles, or consumed as a main course with selected olive oil. Cucumbers were eaten fresh, seasoned with vinegar and garum, and also served boiled with chicken and fish.

From beans, chickpeas, peas, lupins, they made mainly porridges and stews, which were eaten only by peasants, legionnaires and gladiators. Legumes were generally viewed as inconsistent with the position of the nobility: 76: XIII, 7: II, 3, 182, and only imported lentils were considered gourmet worthy.

Many shrubs and herbs were also eaten, which were boiled until they turned into mousse and were served strongly seasoned with vinegar, olive oil, pepper or garum, for example, elderberry, mallow, quinoa, hay fenugreek, nettle, sour sorrel, woodruff, white leaves and black mustard, parsnip leaves, lamb. Viper Bow (bulbus traditionally translated as "onion") was eaten and considered an aphrodisiac: XIII, 34: III, 75:21.

Fresco depicting kitchen utensils. House of Julia Felix, Pompeii

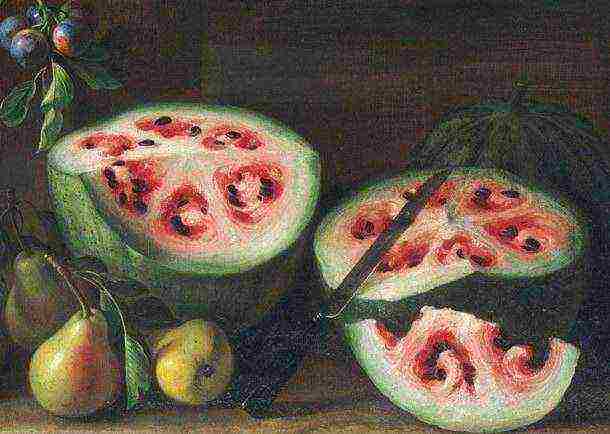

Fruits

Traditionally, the Romans ate pears, cherries, plums, pomegranates, quince, figs, grapes and apples (there were up to 32 types of cultivated apple trees: 63). In the 1st century BC. NS. oriental fruits appeared in the gardens of Italy: cherries, peaches and apricots. Fruits were consumed fresh, preserved in honey or grape juice, dried, as well as in main courses and snacks; for example, Apicius describes recipes for peach and pear casseroles.

Condiments

In ancient Rome, the practice was widespread to drown out the taste of food consumed with garum sauce and various seasonings. Olive oil, vinegar, salt, honey were used as food spices. The following spices were used from local plants: seeds of dill, anise, mustard, marjoram, celery. Imported spices: parsley from Macedonia, cumin from Syria and Ethiopia, thyme from Thrace, ginger, cinnamon, black pepper from India. The most popular spices were garum sauce, pepper (black, white, long), sylphium - a milky plant with a pungent taste that became extinct already in the 1st century AD. BC, probably due to the large collection of this plant, including roots, which were valued on a par with silver: 110. Garum is a sauce made from fish. There were various options for garum - with water (hydrogarum), wine (oenogarum), vinegar (oxygarum), peppery (garum piperatum) or with spices. In all Apicius recipes, garum was included in the dishes, only in three recipes - salt.

Apicius considers pepper to be the most important seasoning and recommends adding it to poultry, peas, as well as boiled and fried eggs. Pepper was often used in recipes at the same time as honey. Pliny the Elder criticized the use of this seasoning, since, in his opinion, it is added only because of its pungency and because it is brought from India. Some criminal pepper dealers "diluted" the seasoning with juniper berries, mustard seeds, or even lead powder: 46. Before the widespread distribution of pepper among the population (around the 1st century), the Romans added myrtle or juniper berries to their food to add spice.

Gardens and vegetable gardens

For a long time in the city, the poor had the opportunity to grow vegetables in the beds: women grew "penny vegetables", Pliny the Elder called the vegetable garden "the poor man's market." Later, with the rapid growth of the urban population, the poor were forced to buy vegetables from the Vegetable Market: 74. Commercial vegetable gardens appeared, the workers of which were able to breed "cabbage of such a size that it did not fit on the table of the poor man." Each peasant household also had its own vegetable garden. Vegetables and fruits were brought to Rome from the gardens and orchards of Lazia and Campania.

For the wealthy Romans, more refined varieties of simple vegetables were grown, for example, the plebeian food - the garden bean - was cultivated to the variety Baiana (Bayan beans), the poor ate common cabbage, young cabbage stalks and shoots were served for gourmets, asparagus grew in the wild, but a cultivated variety of asparagus was grown for an exquisite taste (asparagus):76.

Roman gourmets experimented with crossing varieties, but only two new types of fruit trees were able to grow: Pliny the Elder mentions crossing a plum and an almond tree and an apple tree with an almond tree. Thus, on the gourmet table appeared and even became popular in Rome "almond plums" (prunum amygdalinum), "Apple plums" (prunum malinum):200.

Canning

For salting vegetables such as cabbage, capers, celery roots, rue, asparagus, young, onions, various types of salad, pumpkin, cucumbers, brine, vinegar or a mixture of brine and vinegar (2/3 of vinegar) were used: 79, with the addition spices such as dried dill and fennel, sylphium, rue, leek, pepper. Sometimes vegetables were canned in vinegar mixed with honey or mustard: 39-40. The olives were preserved in brine, vinegar, fennel and olive oil.

Apples, pears, quinces, pomegranates were covered with hay or sand and kept in the pantry; whole or cut fruits were preserved in vessels with honey, in passum - quince and pear, in grape fruit drinks - quince, pear, mountain ash, in wine - peach. The peach was also soaked in brine, then laid out in vessels and poured with a mixture of salt, vinegar and savory. Mushrooms, onions, mint, coriander, dill, marjoram were dried; apples, pears, cherries, rowan, plum.

The fish was dried, smoked, tuna, sardines, sea carp, mackerel, and sea urchin were salted in barrels. The meat, wrapped in straw and a handkerchief, was kept in a cool place; also dried in the sun or smoked indoors. The Romans salted pork, goat, venison, lamb, beef. Apicius advised to boil hard salted meat first in milk, and then in water: I, 8. In winter, Apicius advises keeping fresh or boiled non-salted meat in honey; in the summer, with this method of storage, the meat remained fresh for only a few days: I, 8: 124.

Import and export of products

All kinds of animals, plants and delicacies for the Roman table were imported from all over the empire. The fashions for different products changed as well as for the furnishings of the tricliniums. Gourmets from the end of the Republic became interested in products from different regions of the then known world. According to Seneca, "animals from all countries are now recognized on the table." Products from different countries began to appear on the Roman's table. Differences in the quality and taste of products depending on the region of production have become well known.

Garum from New Carthage and Lusitania was considered the best in the empire; Spanish olive oil and honey were also appreciated: 103.

The olive tree was initially unknown to the Romans, so, in 500 BC. NS. it was not common in Italy: 76, Etruscans and Romans used animal fats: 135. Later, the Romans began to grow the olive tree. According to scientists, the Romans began to use the fruits of an already cultivated tree for food, and not a wild one. From the 1st century BC NS. olive oil was imported into the Roman provinces; about 20 varieties were grown in Italy. Most of the olive harvest was processed into oil, which was added to salads, sauces, main dishes, and only a small part was salted in vinegar and olive oil and served as a snack.

Cereals and leeks were brought from Egypt, lettuce - from the territory of modern Turkey, tubers and greens of rapunzel - from the territory of modern Germany. In the gardens of Rome cultivated varieties of "African" and "Syrian" apple trees, pears were brought to Italy from Africa and Syria, pears from Alexandria, Greece, Numidian and Syrian were valued. Dates were served for dessert and were also a must-have holiday gift (xenia) on Saturnalia. Very sweet yellow and black Syrian dates grew in Syria and Judea, white little Thebes grew in the arid area around Thebes. At the time of Pliny the Elder, up to 49 varieties of dates were known.

On the Balearic Islands, small cranes and buzzards, sultans were caught, chickens were imported from Rhodes and from Numidia, waterfowl from Parthia, pheasants from Colchis. On the territory of southern Portugal, Andalusia, Mauretania, southern France, Tunisia, handicraft enterprises - predecessors of modern fish factories - produced canned fish - fish fillets or whole in oil and salt. The black tilapia caught from the Nile was highly valued. An ordinary sunflower was imported from southern Spain, from the vicinity of today's Ibiza - sea carp, the best moray eels - from Sicily, sturgeons - from Rhodes, laurels - from the Tiber, red mullet - from the Red Sea, oysters - from Britain and the North Sea. Ham and cheeses were imported from Gaul: II, IV 10/11, meat from the province of Belgica was considered exquisite.

Image of sylphia on a coin from

Cyrene

... Wild Sylphium grew on the Libyan coast and was exported to Rome.

The Romans spread in western and northern Europe such plants as chickpeas, beans, celery, garden quinoa, chard, parsnip, amaranth, which was not grown in northern and western Europe before the Romans. The following food products were not known in ancient Rome: paprika, tomatoes, potatoes, zucchini, almost all varieties of pumpkin, eggplant, spinach, radish.

Taste perception

Onions, garlic and leeks were consumed by the Romans mostly raw. Varro wrote that although the grandfathers and great-grandfathers of the Romans smelled of garlic and onions, they still had wonderful breath, Horace wrote about garlic with hatred, as a product that can be considered as punishment, the worst poison for the intestines.

Towards the end of the Republic, "pungent" vegetables such as onions and radishes, such as onions or radishes, began to disappear from the menus of middle-class and upper-class Romans: 75. Later, garlic remained only in the diet of peasants, poor people and legionnaires. Pliny the Elder calls radish an "obscene" vegetable unworthy of a free man. The Romans knew at least 2 varieties of leeks: 75, which differed in their pungency: after eating the Tarentine leek, Marcial advises to kiss with a closed mouth, and another variety from Ariccia praises it very much: XIII, 18. However, boiled and pickled leeks and onions were part of many Roman recipes: 29.

Obviously, the ancient Romans appreciated a variety of tastes in dishes, for example, they liked combinations of sweet and sour, as well as sweet and peppery: almost all dishes, not excluding meat, vegetable and fish, were added fruits, honey or grape syrup, very rarely - sugar most commonly used in medicines: 42; honey was also added to soups, sauces, desserts, baked goods, mixed with water or wine. Pepper was added to wine, sauces, garum, and often even to fruits: 193.

Poultry, fish, dates, asparagus and seafood. 1st century. Mosaic,

Vatican museums

.

Food prices

Diocletian's edict on maximum prices (beginning of the 4th century AD) established firm prices for food and prices for the work of artisans and other professions (for example, a baker received 50 denarii a day, a canal cleaner - 25, a fresco painter - 150) : Earnings. Prices for some food items by category:

- Poultry, price in denarius per piece: fattened pheasant - 250, fattened goose - 200, peacock - 300 per male, 200 per female, a pair of chickens - 60, duck - 20: Poultry.

- Seafood, price in denarii per libra (327.45 g): sardines - 16, pickled fish - eight, but one oyster for one denarius: Fish.

- Meat, price in denarius per libra (327.45 g): Gallic ham - 20, Lucan sausage - 16, pork - 12, pig's uterus - 24, beef - eight: Meat and sausage.

- Vegetables, price in denarius per piece: carrots - 0.24; cucumber - 0.4; pumpkin - 0.4; cabbage - 0.8; artichoke - 2: Vegetables.

- Fruit, price in denarii per piece: apple - 0.4; peach - 0.4; fig - 0.16; lemon - 25: Fruit.

- Liquid products, price in denarius per sextarius (0.547 l): olive oil - 40, garum - 16, honey - 40, wine vinegar - 6: Oils, etc.

Recipes

From the Greeks, the Romans adopted many cooking techniques, recipes and names for dishes and kitchen utensils.Often the recipes were named after the chefs or gourmets who prepared them: 186, for example, "peas a la Vitellius" stewed with mallow (V, 3, 9), "chicken a la Heliogabal" with white milk sauce, "pea chowder a la Apicius "with sausage, pork, ham (V, 4, 2). Apicius' cookbook "On the art of cooking" lists dishes that combine recipes and products from different regions of the world: Alexandrian pumpkin with honey and pine grains; lamb filled with savory and damask plums; ostrich with two varieties of dates and Indian peas with squid and octopus, seasoned with wine, green onions and coriander (V, 3, 3).

Recipes with “false” foods were popular, for example: salted fish without salted fish (IX, 13), anchovy casserole without anchovies (IV, 2, 12) made from boiled fish, eggs, anemones and spices.

Meat and fish were fried, boiled, made fricassee, meatballs, casseroles, etc. Even in gourmet cuisine, meat was first boiled, only then fried or stewed: 191. Casseroles were prepared from cheese, meat and fish, vegetables and fruits; fricassee - from fish, meat, offal. Sauces were served with almost all dishes and were sometimes prepared in advance; for color, saffron, passum, syrup from figs were added to sauces and dishes.

Food intake

The main dish was the pulse - a thick spelled porridge cooked in water or milk: 14. This dish was so typical of the Romans that Plautus called the Romans "kasheedami" (pultiphagones): 54. Fresh or boiled vegetables and legumes were used for porridge.

Initially, breakfast was served in the morning (ientaculum / iantaculum), at lunch (prandium) - second breakfast, after lunch the main meal - cena, and in the evening - vesperna... Influenced by Greek traditions as well as the increasing use of imported goods cena became more and more plentiful and began to be performed in the afternoon. Second breakfast was served at about noon, prandium was also commonplace. The lower classes retained the tradition of all meals, which rather corresponded to the needs of the working person. Meanwhile, the Romans also had a snack - merenda - earlier this was the name of the evening meal of the slaves, later - any meal without special preparations: 194.

Breakfast

Breakfast was the easiest meal of a Roman and depended on the type of work, daily routine and social status. Breakfast usually took place between 8-9 am. Initially, the Romans ate spelled cakes with salt, eggs, cheese, honey for breakfast, and sometimes olives, dates, vegetables, and meat and fish in wealthy houses. Cheese mixture with garlic, butter, celery, coriander - moretum was willingly consumed with bread. From the time of the empire or from the beginning of our era, the Romans ate wheat bread and, over time, an increasingly varied pastry, which replaced the flatbread. For example, the verses of Martial belong to the second half of the 1st century AD:

Get up: the baker is already selling the boys breakfast, The voice of morning birds with a comb is already heard everywhere.- Martial. Epigrams. Book. XIV, 223

Drinks for breakfast included water, rarely milk and wine.

Dinner

This word was used by the Romans for a light lunch or snack at 12-13 hours. Mostly cold snacks were served for lunch, such as ham, bread, olives, cheese, mushrooms, vegetables and fruits (dates), nuts. Lunch was more varied than breakfast, but still had little importance, so some Romans had a snack while standing. Sometimes food left over from the previous day's supper was warmed up for lunch. Wine with honey was served as a drink. After dinner, in the hot summer, began, at least for the upper class and soldiers, a siesta (meridiatio) lasting 1-2 hours. Schools and shops were also closed at lunchtime.

Dinner

In the upper classes, whose representatives did not work physically, it was customary to settle matters before lunch. After lunch, the last business in the city was completed, then they went to the baths, and between 14-16 hours dinner began. Sometimes dinner dragged on until late at night and ended in booze.

| Roman dinner:

1: XI, 52: Snack: onions, lettuce, tuna, eggs with rue leaf, eggs, cheese, olives; Main dish: fish, oysters, pig udders, poultry. 2: Snack: salad, three snails and two eggs per person Main dish: porridge made from pearl barley and spelled Dessert: olives, chard, cucumbers, onions 3: V, 78: Snack: lettuce, leek, tuna with eggs Main dish: green cabbage, sausages in white flour sauce, beans with bacon Dessert: dried grapes, pears, chestnuts |

The duration of the dinner, the number of dishes served, as well as the entertainment part depended not only on personal taste, but also on the social status of the owner of the house. Especially varied were the dishes served at the dinner party - convivium, to which guests were invited according to special criteria. If the dinner was held in a family circle, then close friends or acquaintances were also invited to it. In this case, the food was simpler and consisted of hot meat or fish dishes, snacks, vegetables.

In the days of the kings and the early republic, in all classes, dinner was very simple: it consisted of cereal from grain - the pulse. The simplest recipe for such porridge: spelled, water and fat or oil, sometimes with the addition of vegetables (for example, inexpensive cabbage): XI, 77. The richer segments of the population ate porridge with eggs, cheese and honey. Occasionally, meat or fish was served to the pulse. Later, nothing changed for the majority of the population, meat was served only on holidays. Many ate at cheap eateries or bought food on the street, as they did not have the opportunity to cook in the narrow apartments in the insula.

In the republican period, the dinner of the middle and upper class consisted of two parts: the main course and dessert with fruits and vegetables, and in the days of the empire it was already in three parts: the appetizer, the main course and the dessert. TO appetizer (gustatio, gustus, antecoena) included light, appetite-inducing dishes, served wine mixed with water and honey, - mulsum - mulsumwhich, according to Horace, washed the insides before eating: II, 4, 26, so the appetizer was also called - promulsis... The appetizer included chicken, duck, goose eggs, less often peacock eggs. Fruits in sour sauce, salted olives in oil, and spiced olive paste, appetite-appealing vegetables such as leeks, onions, cucumbers, capers and watercress were also served. Other appetizers also included mushrooms, especially Caesar mushroom, porcini mushroom, champignons, and truffles. Stewed and salted snails, raw or boiled shellfish, sea urchins and small fish were also eaten. At the end of the republic's existence, small meat snacks were served, for example, dormouse, which were grown in special fences, gliraria... Later, sausages, fish and fricassee were also served with appetizers.

Main dish (mensae primae, same caput cenae) usually consisted of meat and vegetables. Sausages, pork dishes, boiled and fried veal, baked and stuffed poultry, game were served as meat dishes, and later fish began to be served. Garnish in the modern sense did not exist, however, in all classes, bread has been used since the Romans began to grow wheat. Only the poorest, who did not have stoves, still ate porridge, which could be easily cooked on the brazier used to heat the insula. Later, with the proliferation of public bakeries, the poor also began to eat purchased or given as a free allowance bread. Garum sauce and various spices were served with various dishes.

Fruit bowl. Fresco from the house of "Julia Felix", Pompeii

On the dessert (mensae secundae) at the end of the dinner, fresh fruits and dried fruits, nuts, pastries were served. Previously used as a dessert, oysters eventually became part of the appetizers. An important role was played by pies, often made from wheat with honey.

Food culture

Originally, the ancient Romans ate in the atrium, sitting by the hearth: 21. Only the father had the right to recline, the mother sat at the feet of his bed, and the children were placed on benches, sometimes at a special table, on which small portions were served to them. Slaves were in the same room on wooden benches or eating around the hearth: 194.

Later, they began to arrange special halls - triclinies - for dinner parties, in which wives with children began to take part, they were also allowed to eat while lying down.Initially, this word denoted three-seater dining couches (wedges) installed with the letter P, then the name was assigned to the very premise of the dining room: 23. Sometimes several tricliniums were arranged in one dining room. Rich houses had several dining rooms for different seasons. The winter triclinium was often placed on the lower floor, for the summer the dining room was moved to the upper floor, or the dining bed was placed in a gazebo, under a canopy of greenery, in the yard or in the garden. Often, garden triclinia were fenced off with a wall, instead of sofas there were stone beds and tables.

Furniture

The Romans adopted the custom of eating lying down from the Greeks (around the 2nd century BC after the campaigns to the East). With this tradition, furniture came to Ancient Rome: klinia and triclinia - three klinia that surrounded a small table for food and drinks on three sides. Each of the boxes in the triclinium had its own designation: in the middle lectus medius, to the right of the central line lectus summus and left lectus imus... The owner of the house with his family was located on the lower (left) wedge, the other two were intended for guests, and the most important guests were placed on the middle bed. The most honorable place on each box was the left one, with the exception of the middle box, where the right one was considered to be the place of honor, which was located next to the owner's place.

Each wedge was designed for a maximum of three people: 195. If someone brought with him an unexpected guest (his "shadow") - or in the case of a lack of space on the boxes - chairs were placed in the wedge; the slaves were often standing all the time. Subsequently, several tricliniums could be installed in the dining room at once. Already at the time of the Roman Republic, nine boxes for 27 people began to be erected in tricliniums.

Varieties of wedges: fulcrum - wedge with a raised headboard, so that the illusion of a wall was created; lectus triclinaris with elevations at the head and legs; plutens - a sofa known since the 1st century (usually 215 cm long and 115 cm wide) with walls 40-50 cm high on three sides; stibadium - a horseshoe-shaped sofa, comfortable for a larger number of guests, became popular in the 3rd-4th centuries.

Each bed was a wooden or stone scaffold with a slope away from the table; they were covered with mattresses and blankets. All three boxes were of the same length and each had three seats. The seats were separated from each other by a pillow or a headboard stuffed with something; the higher edge of the bed, adjacent to the table, rose slightly above its level. The diners lay down in their place obliquely, resting their upper torso on the left elbow and headboard, and their legs stretched out to the right side. This situation changed more than once during a long meal: 195. Eating in a recumbent position may seem uncomfortable to a modern person, but to the Romans this position seemed most appropriate for a quiet enjoyment of food. The tradition of eating lying down did not spread to all Roman provinces, as evidenced by some images of Roman feasts: 359.

By the end of the republic's existence, round and oval tables began to come into use. Around such a table, they began to arrange one bed in the form of a semicircle - sigma (a bed for 5-8 people, curved in the shape of the Greek letter Sigma) or stibadium (a semicircular bed that could only accommodate six or seven people). The seats on the bed were not separated by pillows; around the entire sigma there was one pillow in the form of a roller, on which everyone reclined. The bed itself was still covered with carpets. On sigma, the places of honor were extreme; the first place was on the right edge, the second on the left; other places were counted from left to right.

The tables of the rich were made of citrus wood, maple or ivory: XI, 110. From the 1st century, tables began to be covered with tablecloths, before slaves simply wiped the tables after eating.

Cutlery and crockery

In most ancient Roman households, dishes were made of cheap wood or clay, and wooden dishes have not survived to this day. Wealthier ate from dishes terra sigillata - made of red clay with a matte or smooth surface, which at first (1st century BC.BC) was rare and expensive, but with the spread of this type of pottery in the northern provinces, it lost its exclusivity. Items made of thin glass and cutlery made of bronze began to be appreciated, items made of silver were most valued. The largest set of silverware of 180 items was found in the house of Menander in Pompeii: 140. The Romans also used lead utensils: 40.

2 types of spoons were used: large (ligula), more like modern teaspoons, and small (cochlearia), with a round cup and a long handle, for eating eggs and snails. The handle also served as a modern fork. At the table, large pieces were cut / cut, small ones could be taken from cups and trays. The fork was known to the Romans, but was only used to lay out dishes.

For drinks used: cantharus - a cup with two handles on a leg, cymbium - a boat-shaped bowl without handles, patĕra- a flat bowl, used primarily in cult rituals; calix - a cup with handles; scyphus - a cup without handles; phiăla - a bowl with a wide bottom; scaphium - a boat-shaped bowl.

Tradition and etiquette

Invitations to guests were delivered or handed over in person; clients were often handed out by slaves on behalf of the owner. The feast organizers insisted that important guests bring friends with them: 125. Representatives of the same class with the owner of the house were expected to accept an invitation to dinner (except, for example, days of personal mourning: 31). When a guest was invited to dinner by members of the lower classes, he could decline the invitation for "unimportance." In his epigrams, Martial describes the type of "invitation hunter" who knows where and at what time you need to be in order to be invited to dinner or a banquet that same evening. A certain Wakerra in the epigram of Martial spent several hours for this purpose in latrine: XI, 77.

They took off the toga at home and put on special clothes for eating (synthesis or vestis cenatoria) - comfortable garments made of printed chintz or silk. In the master's house, guests took off their shoes, independently or with the help of a slave. Before eating, the Romans washed their hands, often their feet. They also washed their hands after each dish, because, despite the existence of cutlery, they ate traditionally with their hands, grabbing pieces of food from the common dish; spoons were used only for flour products and sauces. To wash their hands, the slaves brought a bowl of water. Good manners at the table were considered: do not blow on food, gently and "appetizing" to take pieces of the dish with your fingertips and gently bring them to your mouth.

A kind of mouth wipe was also used. After the completion of the meal, the guests wrapped them in gifts from the owner (apophoreta), for example, ointment or perfume, dessert or food leftovers: 667. Martial dedicated apophoreta a cycle of 208 couplets of the same name, each of which briefly describes the gift received. From this list one can judge how much the gifts varied depending on the condition and taste of the owners: silver Minerva (179); Asturian pacer (199); the book of Titus Livy on parchment (190); gallic dog, cursive slave (208), tooth powder (56).

Inedible food waste - bones, lettuce, nut shells, grape seeds, etc. - were thrown on the floor, then the slaves swept the so-called "collected": 9.

Getting up from the couch to go to the toilet was against the tradition of a feast. Still, they went to the toilet outside the dining room, so if a guest or owner did not leave the bed and demanded a pot for emptying, then this was considered an unheard-of violation of etiquette. The use of emetics (warm water, water with honey or salt: I 3, 22) did not belong to the traditions of the feast, even among aristocrats, only a small part of the upper class sometimes used emetics during prolonged receptions. Also it was impatient to "let the gases in". In the satire, Petronius Trimalchio, as a generous host, against the rules of etiquette, allows this to his guests: XLVII, 5.

During the dinner and feast, mimes, musicians, acrobats, trained monkeys, magicians, dancers performed, belly dancing was popular: XI, 162, sometimes gladiators even fought, some of the hosts sang or read aloud themselves, had conversations at the table, played dice or grandmothers, in lots (sometimes expensive gifts such as clothes, dishes, musical instruments, weapons, and also slaves were played): 667, in board games.

At the feasts by the end of the republic, married women were allowed to be present, during the time of the empire also unmarried women.

Feast scene. Fresco from Pompeii, 1st century. According to some scholars, women of easy virtue are depicted in the scenes of banquets on the reliefs of Pompeii (judging by their clothing, but rather its absence, and postures)

:22, 67

.

Very few sources have survived about the traditions of the feast among the common people. At the beginning of the meal, they said a prayer to the gods, and before dessert they made a sacrifice to larams - pieces of salt. In wealthy homes, sacrifices were also made to laras before dessert, usually meat, pie, often garnished with saffron, and wine.

Drinks and drinking culture

The most popular drinks of the Romans of all segments of the population during the meal were water and wine: 397. The access of the citizens of Rome to clean water did not depend on the season and was provided stably since the construction of the first water supply systems in the 3rd century BC. NS.

When wine was consumed as a drink, it was usually diluted with water, while undiluted wine was used primarily in cooking, for example, in making sauces. The Romans distinguished by color white and red wine, Pliny gives four colors: "white, yellow, blood red and black." In Rome, both local and imported wine were used, old, aged wine was highly valued. Wanting to give the wine a more complex taste, sometimes rose or violet petals, aloe or myrtle leaves, juniper, bay leaves, wormwood, or even incense (backgammon or myrrh) were added to it. In summer, the wine was cooled with ice from special cellars or in amphorae with double walls, into which water was poured for cooling; in winter, wine was often warmed up in vessels similar to a samovar.

Cup. Mosaic from the Bardo Museum, Tunisia.

Various wine drinks were also prepared: passum (passum) - wine made from dried grapes, defrutum (defrutum / defritum) or glanders (sapa) - boiled grape fruit drinks, Laura - wine from grape pomace, mulsum - a dark red drink made from fresh grape juice and honey in a 4: 1 ratio. The Romans mainly borrowed the technology of growing grapes and making wine from the Greek experience, some Romans also drank wine "according to Greek custom" (according to the Romans), that is, undiluted (see also Ancient Roman Cuisine and Health). There was also a recipe like the modern mulled wine - conditum paradoxum - a mixture of wine, honey, pepper, bay leaves, dates, mastic resin and saffron, which was cooked several times and consumed hot or cold.

Comissatio

After the main feast and before dessert, sacrifices were made to the larams: the altar was washed with undiluted wine. During the whole main feast, they drank in moderation, believing that wine interferes with fully enjoying the food: 197.

On republican customs and laws, Cato the Elder writes that a husband could condemn or even kill his wife if she drank wine, then laws appeared forbidding women to drink wine. During the empire, women were allowed to attend receptions and feasts. Seneca writes that women drink as much as men.

Food in different classes

Middle and upper class

The wealthy Romans were influenced by Greek traditions. With the growth of prosperity, food became richer and more varied. Nutritional value was at the same time of secondary importance - gourmets preferred dishes with low calorie content and low content of nutrients, in general, gourmets appreciated everything exotic and extravagant; for gourmets, it was rather the inaccessibility of the product and the high price that mattered: 668. Gluttony, gourmand and luxury of feasts belonged to the lifestyle of the aristocratic minority in ancient Rome during the empire.

Slaves prepared food in wealthy homes.Some of Rome's famous chefs were also slaves, or free chefs served for big money in wealthy homes: 123. Even the kitchens of large houses were cramped and dark, and there was not always an air outlet in them. Often in such houses outside the kitchen (usually in the courtyard) there was a place with a stove and tables where it was possible to prepare receptions (for example, in the Villa of the Mysteries, the houses of Faun and Vetiev): 28-29. Water in the kitchen was constantly flowing: clean water was taken for cooking and drinking, as well as washing, dirty water flowed into latrina.

Large multi-storey buildings on the lower floors housed comfortable apartments with a kitchen and a dining room. In some of these houses, there was one common kitchen with an oven on the floor, but for the poor, this was great comfort. So, in most of Ostia's residential buildings, kitchens were not found: 30. In apartments without a kitchen, they sometimes cooked on portable terracotta ovens. The poor and peasants ate very modestly. Since meat was expensive (the price of a libra of meat could reach the daily wages of a worker), most were forced vegetarians, eating it only on holidays.

Poor urban population

The main food of the poor urban population, like the peasants and slaves, was bread and vegetables. Craftsmen ate beans, adding cabbage and beets to them: XIII, 13, which Persius called the "plebeian vegetable." A modest plebeian dinner included cheap salted fish, boiled lupins, bean porridge with bacon, cabbage, and Swiss chard. Such porridge, as well as salted fish and sausages, was sold on the streets by hawkers from taverns: I, 41. 8-10. The poor could afford meat and fresh fish only occasionally: 74.

Poor people from "funeral partnerships" celebrated memorable days for the partnership, for example, the birthdays of the patrons of the partnership and the day of its foundation, with festive dinners. The stewards of such a dinner (magister cenarum) prepared an amphora of good wine and, in accordance with the number of members, loaves worth two asses each and four sardines per person.

Until 270 AD, grain was given free to the poor in Rome (see also the Bread Laws), not necessarily for baking bread, but rather for making porridge. Later, the poor also began to receive free olive oil, bread instead of grain under Aurelian, and modest cuts of pork.

Reconstruction of Roman cuisine.

Clients

In the literature of the 1st century A.D. NS. sumptuous dinners are often described, characterized by an abundance and rudeness of morals. The wealthy aristocrat invited clients to his dinner, but the host and the guests ate different foods. Viron, the hero of the 5th satire of Juvenal: Satyr 5, was served fine bread made from the best wheat flour, lobster with asparagus, red beard caught near Corsica or Tauromenia, moray eel from the Sicilian Strait, goose liver, "fattened chicken the size of a goose" and a wild boar, "what a spear of Meleager would be worth." At that time, the guests gnawed moldy pieces of stale bread, poured oil on the cabbage, which was suitable only for lamps, and in addition, each received one crayfish with half an egg, eels from the Tiber, a half-gnawed hare and apples in black spots that monkeys gnaw.

There were no canteens or kitchens in the city insuls, so clients received food at the patron's table during their daily morning visit. With the growing number of customers who lined up in the morning, it became impossible to continue this tradition at the family table, so they began to receive each time a “basket” of groceries (sportula):201.

Peasants and slaves

The abundance and variety of peasant food depended on many factors - the loss of livestock, crop failure, the death of the main worker could reduce a strong peasant household to an almost beggarly existence. Cato in his treatise "On Agriculture" indicates how much grain, bread and wine to give to the workers of the estate and slaves: 57:

| 0,9 | 1 | 0,7 | No | No |

| No | No | No | 1,3 | 1,6 |

| 0,57 | 0,57 | 0,57 | 0,72 | 0,72 |

| 0,54 | 0,54 | 0,54 | 0,54 | 0,54 |

The laborers and slaves also received salted olives, vinegar, and cheap salted fish. Since the local wine was very cheap, even slaves were allowed to drink it.

The peasants ate onions and leeks, chicory, watercress, fennel, garden purslane, lettuce, olives, beans, lentils, and peas. A thick stew was cooked from beans and pods (conchis), which was also eaten with bacon. Ovid believed that simple peasant food was to the taste and the goddess: 370.

Legionnaires

In the Republican army, the legionnaires' marching diet included the same everyday products as the common population, which could be stored for a long time, easily transported and simply prepared: 86. In the days of the empire, crackers, posca and long-stored bacon began to be included in the diet. The bread was baked in a square shape for easier transportation. In the camp rations, cereals were necessarily present: barley, spelled, wheat, emmer. The legionnaire's ration included: crackers for three days, fresh bread, bacon, hard cheese, garlic, some fresh meat. In addition, each group of eight legionnaires (contubernalswho had a common tent) had their own frying pan, which allowed them to fry their own food even on a hike.

The legionnaires' food during their stay at the camp included pork, beef, goat meat, game, vegetable stew, cereal, etc. Accounts from the British camp of Windoland show that Roman soldiers ate a lot of ham. On holidays or in honor of great victories, exquisite dishes were served - suckling pig, oysters, good wines. The commanders of the legions, like other wealthy Romans, ate deer and wild boar. Archaeological evidence suggests that guinea fowls, chickens and rabbits were also included in the diet of Roman legionnaires in Roman Britain.

Gladiators

A special diet was prescribed to gladiators, according to which they were called "barley eaters" (hordearii). Bean porridge with a decoction of barley grits helped to gain weight so that the fat layer protects the nerves and blood vessels when injured.

Galen writes that the gladiators also received bread, goat cheese, pork and beef. Studies of the remains of gladiators from graves in Ephesus indicate that gladiators were mostly vegetarians.

Round bread with incisions to make it easier to break. Pompeii.

Sacrifices

The sacrifice to the larams, patrons of the hearth, was usually brought before the dessert was served: wine, laurel, herbs, incense, as well as fruits, honey, salt, porridge and other products were burned on the home altar. A pie with spices and honey was baked especially for the sacrifice (liba). According to Ovid, God (Bacchus) tastes sweet juices: 729. The common people sacrificed pieces of salt to the laras, and to the penates a small portion of food in a cup. To commemorate deceased relatives, bread, fruit, cake, wine, as well as incense and flowers were brought to the burial site: 537, rich families also had a meal. The peasants sacrificed the first fruits and vegetables to the gods. Animals were also sacrificed - bulls, lambs, sheep, as well as cows, pigs, sometimes goats, dogs, horses, chickens: 271. The entrails were cut, boiled, cut into small pieces and burned on the altar, the rest of the meat was prepared and consumed as sacrificial food.

According to the tradition of the ancestors, the Romans of the empire era baked a sacrificial cake from emmer, not cultivated wheat, sacrificial animals were sprinkled with salted emmer flour, an offering to the gods was porridge made from green beans (puls fabata):81.

Fast food in ancient Rome

See also articles: kaupon, popin, thermopoly.

Fast food establishments in ancient Rome were visited by ordinary people from the lower classes (slaves, freedmen, sailors, porters, artisans, day laborers, and, according to Juvenal, also bandits, thieves, runaway slaves, executioners and undertakers: satire 8), who did not have the opportunity cook in their cramped quarters, as well as working people and travelers.Only occasionally did aristocrats appear in such institutions, and those who were recognized could lose the respect of society, this fact could be used by political opponents. Diners and bars served not only for eating, but also for communication and entertainment, dice games, performances of dancers or singers were practiced. Many Romans were frequent visitors to their favorite establishments. The owners also "advertised" their establishments with poems and frescoes at the entrance to the establishment or also guaranteed fixed prices.

Bars and eateries were filled sooner in the evening and were open until nightfall, many were open during the day, especially those located near the thermal baths (in the imperial period - also in the thermal baths) or other places of mass entertainment.

Fresco on the right: travelers - visitors of Thermopoly, sitting at a table, in the lower right corner - offering food. There are sausages and cheeses hanging on the wall

:19

Osteria della via di Mercurio ... Pompeii.

Inexpensive Italian wine was served in taverns, in Gaul also beer, olives or other snacks; ate standing or sitting at a table. Popinas served peas, beans, onions, cucumbers, eggs, cheese, fruits depending on the season, several meat dishes for wealthier customers, pies and pastries: 130. Some emperors tried to limit the range of dishes served, thereby trying to limit the "luxury" and observe the ancient customs, when food was prepared only at home, in addition, taverns could always serve as a gathering place for dissatisfied people. So, Tiberius forbade the sale of bread and pastries, under Nero it was forbidden to sell "boiled food, except vegetables and herbs", under Vespasian it was allowed to sell only beans: 131.

In Pompeii, many thermopoly and popin 'eateries with stalls overlooking the street have been unearthed. There were deep vessels in the room, in which there were cauldrons with food. Behind the counter were shelves with wine amphorae, as well as goblets, dishes and other kitchen utensils. In such establishments, there was also a stove or hearth, over which a vat of warm water hung, so that the guest, at his request, could dilute the wine with warm water or water from a spring. Meat was grilled over the hearth for those who could afford to buy it. Behind the main room there were small pantries for storing supplies, as well as a guest room, in which they also dined, but already with service: 20. In such rooms there was only the most necessary furniture - chairs and a table, shelves, sausages, cheese and fruits hung on hooks on the wall. Prostitutes often offered their services in booties in such rooms: 18. Inscriptions from Pompeii and testimonies of Roman authors indicate that the "barmaids" and "waitresses", and sometimes the hostess of the establishment, also engaged in prostitution: 130.

On the streets, traders sold bread and pastries that were baked in the city's large bakeries. Some vendors sold food on the street from a portable cauldron. Restaurants in the modern sense did not exist in the Roman Empire.

Ancient roman feast

Dinners with friends during the time of Pliny and Cicero were an important part of the life of the ancient Roman aristocracy. Banquets were held not only on the occasion of a birthday or a wedding, but rather were part of the daily routine along with receiving clients or visiting the forum and the term. According to Cicero, for Cato the Elder, the meaning of the feast was to communicate with friends and conduct a conversation. At feasts in the house of an aristocrat, guests of various positions gathered: relatives, friends, clients, freedmen, women - the mistress of the house, the wives of the guests, as well as children, especially sons. The service, the place and the dishes served to the guests strictly corresponded to their position in society.

The most famous description of the feast in Latin literature of the 1st century is found in the Satyricon by Petronius the Arbitrator, where the feast of the wealthy freedman Trimalchio is presented in a satirical manner.Guests were served 62 dishes, for example, a wooden chicken on peacock eggs, inside of which were fatty wine berries, with a sauce of pepper and egg yolk, Falernian wine (counterfeit, as Petronius hints), wild boar stuffed with blood and fried sausages, etc.

On a round dish, the 12 signs of the zodiac were depicted as a ring, and on each of them the kitchen architect placed the corresponding dishes. Over Aries - sheep peas, over Taurus - pieces of beef, over Gemini - kidneys and testicles, over Cancer - a wreath, over Leo - African figs, over Virgo - the uterus of an unsprouted pig, over Libra - real scales with a hot cake on one bowl and a pie on the other, above Scorpio - a sea fish, above Sagittarius - pop-eyes, above Capricorn - sea crayfish, above Aquarius - a goose, above Pisces - two red beards

.

During the period of the empire, the desire for the luxury of feasts sometimes exceeded all reasonable limits - feasts lasted for days, chefs were sophisticated in preparing dishes unprecedented to taste, entertainment was distinguished by cruelty and excesses. Seneca was outraged that Roman gourmets were ready to "... scour the depths of the sea, beat animals to overload the stomach." And yet it is worth noting that in Rome during the empire, extreme manifestations of gluttony were not rare, but still luxurious feasts were rather an exception, and the daily meals of the Romans passed without much chic.

Serving the feast required numerous personnel: a cook led by a head chef, a "feast organizer", a food supplier, a baker, a pastry chef, a milk biscuit baker, slaves: tidying up the beds in the triclinium; structores - set the table; scissores, carptores - they cut the meat into pieces, put it on the dishes, a special slave gave the dish on the dish a more elegant look: 196; the nomenclator met the guests and called their names to those present, and also pronounced the names of the dishes when serving; individual slaves who brought bowls of water to wash their hands; ministratores brought in dishes; ministri drinks were served; after the feast scoparii removed the remnants of food from the floor. All service personnel were managed tricliniarches.

Feasts of the Emperors

According to Friedlander, the "good" emperors ate simply, and the "bad" ones were distinguished by gluttony or gluttony. Simple bread, fish, cheese and figs were to Augustus' taste; Septimius Sever valued vegetables more than meat. Gluttons are described, for example, the emperors Caligula, Heliogabalus, Vitellius, Maximinus the Thrace. According to the "History of the Augustus", at feasts, Emperor Eliogabal offered his guests a dish made from the brains of six hundred ostriches, at feasts he threw delicacies - for example, goose liver - to dogs, green beans were served with amber, rice was served mixed with pearls, and peas - with gold ... This paradoxical combination Fernandez-Armesto called "culinary surrealism".

Suetonius describes the Emperor Vitellius as a famous glutton. The emperor paid a gigantic sum, which at that time was the price of latifundia, for an outlandish dish of sweet meat, baked birds, pheasant and peacock brains and parrot tongues. The dish “The Shield of Minerva the City-owner”, composed by the emperor, consisted of the liver of the scara fish, pheasant and peacock brains, flamingo tongues, and moray eels milk. Everything necessary for the preparation of this dish was imported from Parthia and Spain. Pliny writes that preparing the "shield" required building an oven in the open air and casting an incredible silver dish. The emperor's brother held a more modest feast, at which 2,000 selected fish and 7,000 birds were served.

The emperors organized the so-called "public feasts" (convivia publica), in which a large number of guests took part - senators, horsemen, as well as persons of the third estate. For example, up to 600 people regularly gathered at Claudius, 100 guests were present at Caligula, and 60 senators with wives at Otho.

At the imperial feasts, guests were served elephant trunks, pies from nightingale and peacock tongues and rooster combs, liver of parrot fish. But an actor named Clodius Aesop became especially famous, who bought sixteen songbirds, trained to speak Latin and Greek, for a fabulous sum of one hundred thousand sesterces at that time, solely in order to put them on a spit and serve to guests. According to the Hungarian researcher Istvan Rat-Vega, “an example of this single plate of a dish opens before us a gap sufficient for us to open the mouth of an abyss of moral decay into which, over time, the whole of imperial Rome will fall».

Roman Feast, 1875. Artist

Roberto Bompiani

depicted in detail the ancient Roman frescoes and marble floor; tables, lamps, armchairs are written according to examples of Greek, Roman and Etruscan finds.

Getty Museum

Women at feasts

Women were allowed to attend the feasts as the hostess of the house or the guest's wife, and they could also attend banquets on their own: 75. Some even returned home unaccompanied by the men after the feast. Free women present at the feasts could thus take part in the social and political life of Rome.

The presence of women at feasts became a topic of Roman literature during the late Republic and during the Empire - in letters, poems, treatises, satyrs and odes: III, 6, 25 comment and criticize, ridicule the behavior of women at feasts in the context of a general decline in morality. Culinary, alcoholic and sexual orgies were used in court as examples of debauchery, and protracted banquets served as metaphors to describe the "moral decay" of the Romans. In court speeches, dishonor was denounced, including with reference to nightly banquets and the presence of women at them.

Authors such as Propertius, Tibullus, Ovid, in verse describe love and sex at feasts - the appearance and behavior of women in these verses differ little from the descriptions of Horace, but the assessment is different: according to these authors, the purpose of feasts is to experience erotic fantasies and desires , as well as meeting lovers. Ovid advises a woman not to drink or eat much, the opposite, in his opinion, is disgusting: 80: I, 229; 243. Propertius approves of the use of wine: “Drink! You're beautiful! There is no harm to you from wine! "

Luxury laws

In the late Republican period of Rome, luxury laws began to appear, limiting the spending of the Romans on feasts, cutlery, and also banning certain foods. Formally, the laws applied to the entire population of the country, but the representatives of the Roman elite skillfully bypassed them: 101. So, if, according to the law of Fannius, it was forbidden to fatten chickens for feasts, then they were replaced by roosters.

- Under Cato, luxury taxes, restraining the excessive luxury of feasts, cutlery, and also served to some extent to recreate the ideal of a simple peasant life.

- Lex orchia de cenis (Orchian Dinner Law, 182 BC) - The Orchian tribune law limited the number of guests at dinner to 103, possibly up to three, in order to prevent political gatherings at dinners: 78.

- Lex fannia (Fannius' law, 161 BC) limited the number of participants in the feast to three, on special days to five; forbade the serving of poultry dishes, with the exception of chickens, which were not specially fed. On holidays (Saturnalia, ludi plebei, ludi Romani), it was allowed to spend 100 asses, on a normal day - up to ten asses, for ten days no more than 30 asses were calculated. The daily rate of consumption of dried and canned meat was determined, the use of vegetables and fruits was not limited. The law extended to all the inhabitants of the city of Rome: 103.

- Lex didia (Law of Didius, 143 BC.) - The restrictions of the Law of Fannia now extended to all residents of Italy, and fines were also provided in case of violation of the law for both hosts and guests.

- Lex aemilia (Law of Emilia, 115 B.C.BC) limited the number and range of dishes (imported poultry, shellfish, hazel dormouse) served at parties and private parties: 660.

- Lex licinia (between 131 and 103 BC, abolished in 97 BC) - the law restored under the dictator Sulla, limiting refectory expenses on holidays to 100 sesterces, for a wedding - 200, on other days - 30: 104 : II, 24.

- Lex antia (71 BC) limited the cost of banquets, in such feasts, according to the law, magistrates could not participate.

- Lex Iulia Caesaris (45 BC) - it is not known exactly how this law limited the feasts of the Romans, but its observance was strictly monitored: soldiers and lictors watched purchases and came to feasts of aristocrats, prohibited products were confiscated: 99.

- Lex Iulia Augusti (18 BC) - on ordinary days it was allowed to spend no more than 200 sesterces for a feast, for holidays - 300, for a wedding - no more than 1000 sesterces: 101.

Cuisine in the ancient Roman provinces

Tacitus in “Germany”: 23 described the food of the Germans as follows: “Their drink is a barley or wheat broth, transformed by fermentation into a kind of wine; those who live near the river also buy wine. Their food is simple: wild fruits, fresh game, curdled milk, and they are saturated with it without any fancy or seasoning. " The Romans knew the recipe for making butter, but did not prepare it and did not even eat it if they found this product from the “barbarians”: 135.

A restored ancient Roman oven found almost intact in

Augusta-Raurica

, Switzerland.

Beef dishes were more readily prepared in Roman Germany than in Italy, where pork was more common. The basis for this conclusion is the finds of animal remains: 97-99.

Wines, olive oil, garum, as well as delicacies - oysters, dates, etc. were imported to the province for the Romans who were there. Fruits and vegetables that could be grown in the conditions of central Europe began to be grown locally. So, with the Romans, products such as garlic, onions, leeks, cabbage, peas, celery, turnips, radishes, asparagus, rosemary, thyme, basil and mint came to Roman Britain, as well as a variety of fruits: apples, grapes, mulberry and cherry. The importation of cherries is the only case that is confirmed by written Roman sources, in other cases it follows from the research of archaeobotanists.

Legionnaires prepared food from various cereals, legumes, pork meat, vegetables: carrots, cabbage, parsnips, lettuce - as well as fruits - peaches, cherries, plums, pears, various berries were used. According to the remains of animals found in urban settlements, for example, in Cologne, it can be judged that the urban population ate rather beef obtained from old animals: 97-99.

In Germany, due to the need for heating, dining rooms in ancient Roman houses were located next to the kitchen or heated bath rooms. Kitchens did not differ from those in Italy; in the north of the empire, large and deep cellars were dug in houses for storing food: 89.

Ancient Roman cuisine and health

Despite the development of Greek medicine, the Romans in the republican period still used the recipes of their traditional medicine and paid attention to proper nutrition, diets, as well as baths and herbal treatments.

Cato gives advice and recipes on how to maintain and improve the health of workers, and advises, for example, the use of various varieties of cabbage, which, in his opinion, not only improves digestion, but also helps those who want to eat and drink a lot at the feast. To do this, you need to eat raw cabbage before and after the feast: 156.

Seneca wrote about numerous diseases caused by gluttony and drunkenness: pallor appears, tremors in the joints, a stretched stomach at dinner, rotting, bile, insensitivity, fatigue, excess weight and, in general, "round dance" pains.Columella wrote that long dinners weaken the body and soul, and even young men after this look powerless and decrepit: I, 116. Seneca the Younger wrote that Hippocrates believed that a woman cannot lose hair and hurt legs from gout, however , according to Seneca's observations, women of his day drink undiluted wine and participate in nightly banquets as men and thereby refute the theory of Hippocrates: 95, 20.

Doctors of the period of the empire recommended drinking only one glass of water as a diet for breakfast: 13, Galen advised a healthy person to eat only once a day, the elderly and sick - 3 times a day. In order to be able to absorb large amounts of food, many took emetic, some before, others after dinner. The use of this remedy was recommended by doctors, for example, Celsus, Galen (before meals) and Arhigen (2-3 times a month): 669. Seneca wrote sarcastically: “The Romans eat to vomit and induce vomiting to eat (Vomunt ut edant, edunt ut vomant)».

Wine, especially for the sick and old, was advised to be diluted with warm water: 343. The consequences of excessive alcohol consumption were also known: Pliny the Elder writes about alcohol dependence, when a person loses his mind and the meaning of life, crimes are committed. The habit of drinking undiluted wine and drinking wine on an empty stomach was considered a sign of alcoholism: 14: CXXII, 6.

Moretum

prepared according to an antique recipe

Some products were considered particularly beneficial to health, for example, honey was recommended for external and internal use for diseases from colds to back pain and poisoning, it was also added to bitter medicines for children, and was included in creams, for example, for wrinkles on the face. Pliny the Elder considered olive oil to be a remedy for headaches, as well as for abscesses in the oral cavity, a hemostatic and a good remedy for skin care. In the book "Materia medica" the doctor Dioscorides recommends as especially useful herbs peppermint, anise, basil, dill, fennel. Sugar from sugar cane from India and Arabia was known to the Romans and used as a medicine.

Ancient Roman and modern cuisine

Nowadays, it is very difficult to repeat the dishes of Roman cuisine described in the recipes of Apicius, since in his recipes there are almost no data on the cooking time of dishes and the dosage of individual ingredients, including seasonings. The food was prepared in this way by intuition and experience. Certain ingredients are not exactly known, for example, garum, a sauce that could be bought ready-made. Some authors recommend using regular or sea salt or Asian fish sauces "nyok-mam" or "nam-pla" for such recipes.

Some seasonings are also no longer available, for example, the sylphia plant, which had become extinct in antiquity, which already then began to be replaced with a spicy seasoning of a similar taste from the asafoetida plant: 110. The most popular spices of ancient Roman cuisine - rue, laser, garum - had an unpleasant smell, and for a modern person such dishes would taste unpleasant: 193.

Some of the plants formerly used in Roman cuisine are no longer cultivated, for example, elecampane tall, strong-smelling, pungent and bitter rhizome of this plant became usable after a complex cooking process with honey, dates or raisins. Even under Cato, several varieties of garden viper onions were known, but then they stopped cultivating it: 19. Celery root in antiquity was not only smaller than modern, but also had a bitter taste, although it was present in many recipes.

There are reprints of the book of Apicius with simplified and modernized recipes (see the list of references).

In culture

Floor mosaic "Unswept floor".

Bardo Museum

, Tunisia.

- In the film adaptation of Fellini's "Satyricon" by Petronius, there is also a scene of the feast of Trimalchio, the culmination of which is the cutting of "Trajan's pig".

- Frescoes

- The Romans were not only passionate gourmets, but also paid great attention to the place where they ate their food. So, the halls, tricliniums (judging by the preserved frescoes in Pompeii and Herculaneum) were also decorated with still lifes depicting vegetables and fruits, bread, game, seafood and poultry, as well as silver and simple dishes, scenes of feasts.

- Frescoes Asaroton (Greek asárotos oíkos - "unclean room"): this is how the floor looked like after an ancient Roman feast. Pergamon artist Sos discovered the unswept floor motif as a still life that became popular for floor mosaics in Roman dining rooms.

- Expressions

- Lucullean banquet - the expression is used as a synonym for a lavish feast and gastronomic delights. Lucius Licinius Lucullus was a wealthy and profligate consul and commander of Ancient Rome and organized luxurious feasts and holidays, which later spoke of all of Rome.

- "From eggs to apples" (ab ovo usque ad mala: I 3, 6) the Romans said when they meant "from beginning to end" or from A to Z. The expression is associated with the dishes served for dinner: eggs for a snack, fruit for dessert.

- The name of the renowned gourmet Apicius has become a household name.

- The dependence of the Roman plebs on the distribution of bread is known by the popular expression "panem et circenses" - "bread and circuses": X, 81.

Historical sources

Historical sources about the cuisine of Ancient Rome include early agricultural treatises, laws on luxury and prices, letters and literary works, medical and cookbooks, as well as the works of some Greek authors who lived in Rome: 10.

Roman authors began to turn to culinary themes from about the 3rd century BC. NS. Various Roman authors praise the good old days of Rome, when people were modest and undemanding: 34: they ate porridge instead of bread, the elders sang to the flute, the young were rather silent. Later, the top of the art of cooking was the ability to "serve food in such a way that no one understands what he is eating": IV, 2. About 1000 recipes of Roman cuisine have survived to this day: 34, mostly in the writings of Cato, Columella and the gourmet cookbook Apicius (about 500 recipes): 9.

- IN the first half of the 2nd century BC NS. Marcus Porcius Cato the Elder was the first to mention certain culinary recipes in his agricultural treatise On Agriculture. In describing simple recipes, Cato the Elder tried to show that with the help of ordinary products from local agriculture, you can prepare a variety of foods and not only eat bread or porridge. His recipes and reflections are not directed directly to the cooks or the wife of the owner of the estate, but to like-minded landowners who, with the help of his advice, could rationally run the farm and at the same time maintain the working spirit of the workers. At the same time, Plautus' comedy "Pseudol" appears, in which the chef complains about the newfangled custom of seasoning dishes with a huge amount of seasonings, "stinking sylph" and "pungent mustard", so that, in his opinion, "cattle will not eat, man is eating!". In his comedies, Plautus mentions both primitive dishes such as porridge and new trendy vegetable dishes with an abundance of herbs. In a fragmentary surviving excerpt from Enny's gastronomic poem Hedyphagetica (Treats), different varieties of fish are listed;

Publication of the book of Apicius. 1709 year.

- IN 1st century BC NS. the first three specialized culinary works of Guy Matiy appear on cooking, fish and preparations. The books of Matiy have not survived to this day, but are mentioned in sources. Varro continues the topic of farming in his treatise On Agriculture. The food, banquets and behavior of the Romans become one of the themes in the letters of Cicero, as well as literary works, for example, Virgil and the satyr Horace. Horace's ideal is thrifty farmers who follow the customs of their ancestors, do not drink expensive wines and eat modestly on vegetables, sometimes eating a piece of homemade ham (“I have never ... on weekdays I have eaten anything other than simple vegetables and a piece of smoked pork!”: II, 2, 115).Antiideal - the townspeople who eat up their fortunes, overeating expensive and rare dishes (“all because they pay for a rare bird in gold, that its tail is colorful and lush; as if it’s all about the tail! But are you eating feathers? ... no better than chicken meat! ”: II, 2, 27).

- The only surviving Roman culinary book of the gourmet Apicius appears in 1st century... Apicius wrote at least 2 cookbooks - general and about sauces, which were constantly reprinted with new recipes and were most likely combined at the end of the 4th century into one book called "De re coquinaria". Of the surviving recipes, 300 belong to Apicius, the rest were taken from treatises on the peasantry, books on diets, etc. The methods of cooking are outlined rather briefly, they describe the preparation of meat and fish, sweet dishes, sauces and vegetables. The book features inexpensive as well as sophisticated luxury dishes such as truffles or entrails. There are several medical books and treatises written during this period, for example, the treatise of the Roman physician Celsus "De Medicina", the book of Scribonia Larga "Prescriptions", which describes medicines and medical recommendations. In the book "On Medicinal Substances" by Dioscorides, a Greek physician who worked in Rome, about 800 herbal preparations and 100 on an animal and mineral basis are described, some information is given about the diet of the Romans. Columella writes about agriculture. An important source of information about agriculture, food, the cultivation and breeding of plants and animals, the traditions and customs of the Romans is the "Natural History" of Pliny the Elder. The literary tradition is continued by the letters of Seneca, the satire of Juvenal and Persia. The description of a banquet given by the wealthy freedman Trimalchion of the Satyricon by Petronius the Arbiter is widely known. In his epigrams, Martial shows the customs and behavior of the Romans at receptions, gives examples of dishes and wines, describes the gifts that were handed out to guests. The poem by an unknown author, Moretum, previously attributed to Virgil, depicts a realistic picture of the life of a poor Roman peasant.